Recalls are an embarrassing time for an automaker and a frustrating one for vehicle owners. Getting that recall letter in the mail usually means the maker of your car screwed up, but at least the issue will usually get fixed and you can continue to enjoy your car. Sometimes an automaker screws up so badly that the only fix is to eliminate every copy of the vehicle in existence. Back in the 1920s, Chevrolet had an early major screw-up with the Copper-Cooled Chevrolet. Chevy tried to cut costs by eliminating a liquid-based cooling system and ended up with a car so underpowered and unreliable that Chevy had to recall and then destroy almost all of them.

Unholy Fails is a series dedicated to highlighting the cars that could have been a Holy Grail one day, but for whatever reason missed the mark. Maybe these vehicles were good ideas saddled with bad engines or a good vehicle just too late to make its mark. Until now, every Unholy Fail entry is a vehicle you could go out and buy right now. I have a feeling it’s going to be a long time before we find another Unholy Fail so bad that you couldn’t even buy the vehicle in question.

Yet, the Copper-Cooled Chevrolet was such a blunder that the automaker tried to erase it from existence. The lead engineer behind the project then offered his resignation. So, what happened?

Setting The Stage

This story takes us back to the 1910s, after Henry Ford caught lightning in a bottle with the affordable Model T. America’s automakers wanted to capture buyers from Ford.

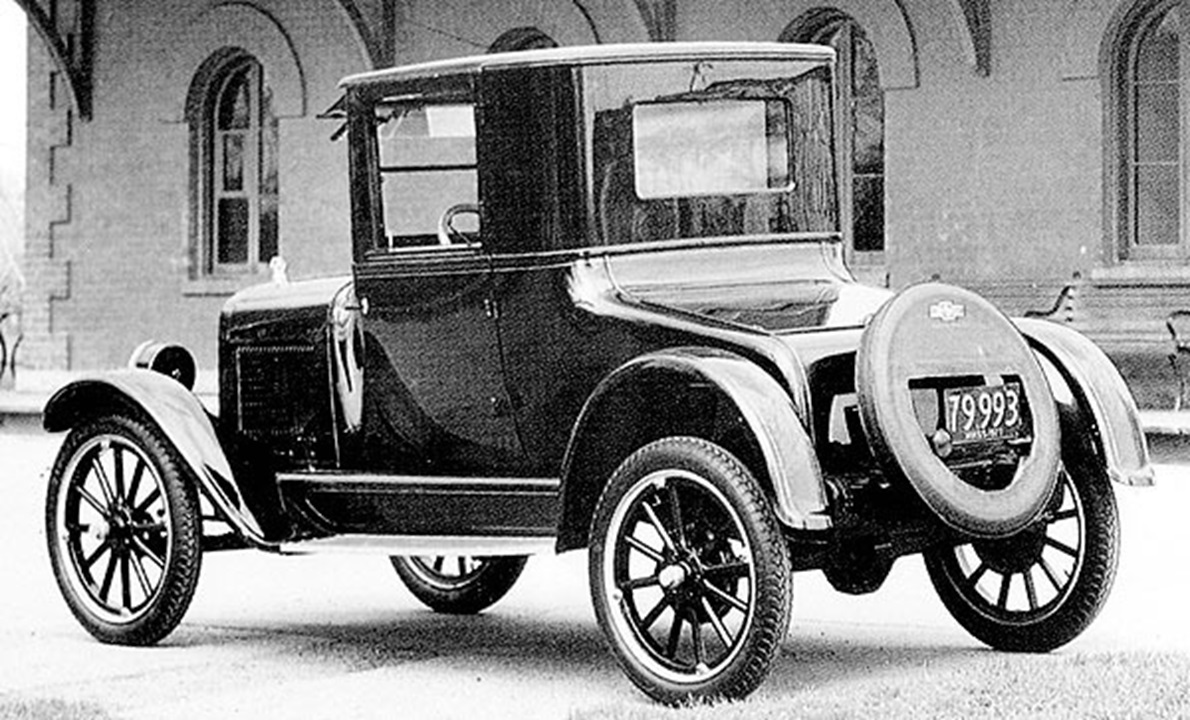

As Hemmings writes, one of those automakers was Chevrolet. The bowtie’s effort to beat the Model T was the 1916 Series 490. Now, Chevy wasn’t very imaginative with this one as it was a conventional vehicle with a name reflecting its $490 price tag. Unfortunately, not only was this car $50 to $100 more expensive than a comparable Model T, but it didn’t seem to justify the price hike. The 490 was the baby of General Motors founder Billy Durant and it struggled to find its place on the market. Eventually, prices for the 490 went up and Chevy just couldn’t compete with the big Blue Oval.

By 1919, Chevrolet found itself under the umbrella of General Motors. Not long after, Durant relinquished control of GM, and in his place were Alfred P. Sloan Jr. and Pierre S. du Pont. The pair shored up GM’s mid-price vehicle production and trimmed the fat within the company. Then it was time to do something about Chevrolet.

It was around this time when Charles F. Kettering was conducting experiments with his latest fascination: The air-cooled engine. Kettering shows up a lot in vehicle history. He served as the president of the board of directors of Flxible for decades. Kettering ran GM’s diesel development program in the 1920s and 1930s. Kettering invented Cadillac’s electric starter, the cash register, an automotive electrical system, a rudimentary guided bomb, and he even had a hand in leaded gasoline. The man, who was the head of Dayton Engineering Laboratories Co. (Delco) had his hands in a lot of different things.

But this was 1918, before GM’s dominance in diesel-electric locomotives and before Kettering would later become chairman of a bus manufacturer. Kettering loved the idea of an air-cooled engine and for good reason. An air-cooled engine does away with a radiator, water pump, and all of the associated plumbing. An air-cooled engine reduces weight and complexity, and important for a Chevy trying to beat Ford, it would also reduce cost.

Air-cooled engines weren’t new in those days, but they were typically found in more expensive vehicles such as Franklin (above) and Holmes cars. The air-cooled engines of those days also relied on cast-iron cooling fins. Kettering thought he was onto something when he came up with an air-cooled engine that would ditch cast iron for copper. On paper, this was a good idea because copper had 10 times the conductivity of iron and was more readily available than aluminum.

Kettering’s love for air cooling got du Pont on board, but Sloan wasn’t convinced GM should get rid of its water-cooled cars. As Hemmings writes, Kettering essentially kicked and screamed about the copper-finned engine every time GM showed any reluctance in allowing the project to move forward. Reportedly, Kettering even pleaded with GM by telling brass that getting rid of the water-cooled parts cost nothing, didn’t come with a weight penalty, and didn’t impact operation.

Eventually, Kettering got his way and it was decided that Chevrolet and Oakland were going to ditch water-cooling for what would be dubbed the Copper-Cooled six-cylinder engine. While Oakland was receptive to the change, Chevrolet General Manager Karl Zimmerschied was unhappy that nobody consulted him before dropping this announcement on him. GM’s brands were largely autonomous during those days and understandably, Zimmerscheid didn’t want this newfangled technology forced on his division, but that wasn’t his call to make as du Pont wanted the 490 replaced as soon as possible.

GM wanted the Copper-Cooled car so much that it planned to kill water-cooled Oakland production in December 1921 before introducing the new car a month later. Unfortunately, cracks showed early on.

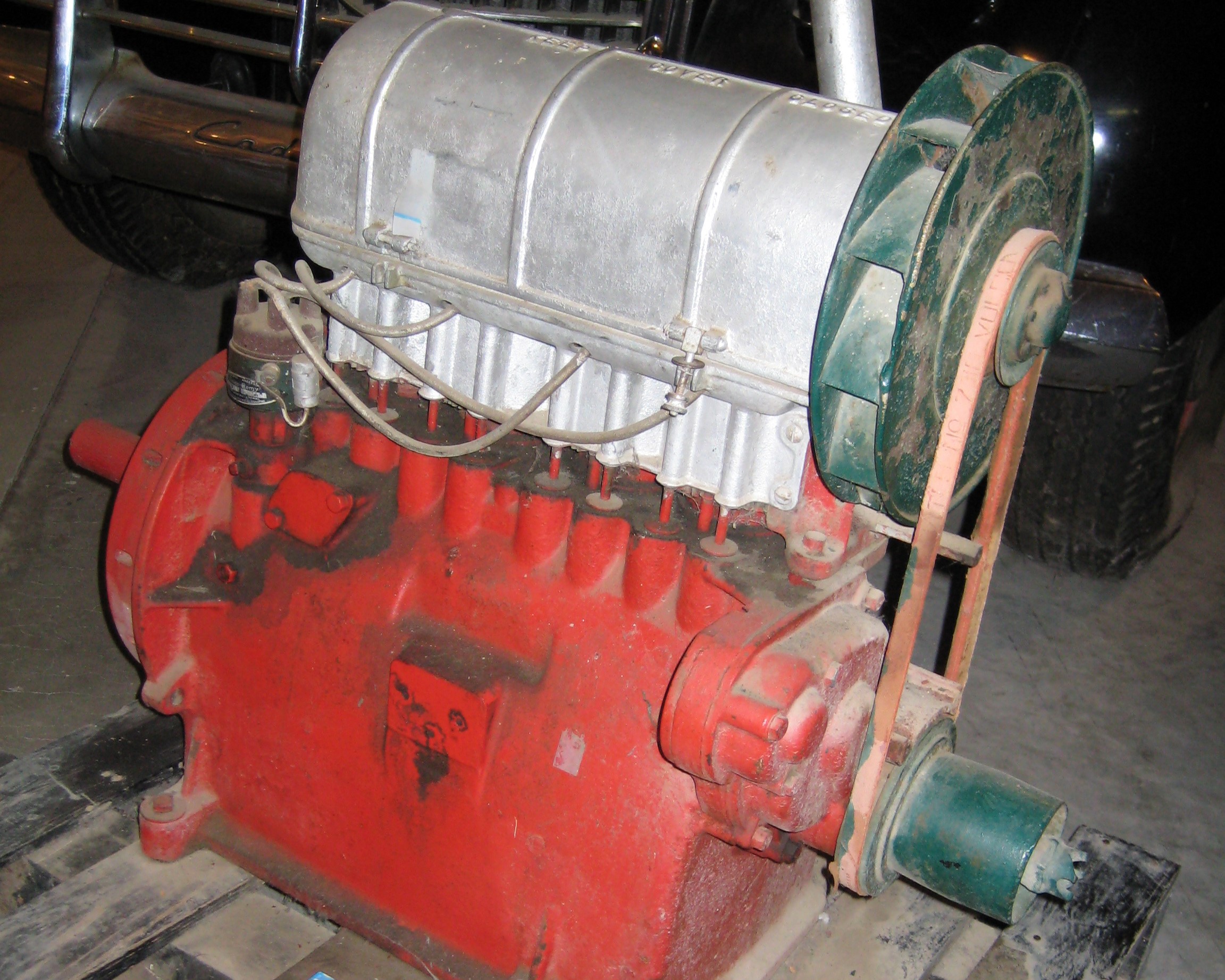

Kettering’s design of the Copper-Cooled engine was, in terms of appearance, similar to the cast-iron air-cooled engines of the day. The engine was covered in sheet metal and used a giant fan for airflow. Where designs departed was in the cooling fins. Kettering went with copper arranged like a heat sink and furnace-brazed onto the engine’s cylinders. As Mac’s Motor City Garage writes, this engine had 5,300 square inches of cooling area compared to the 3,100 square inches found on a larger Franklin engine. Kettering saw this, as well as the use of copper, to be a major breakthrough in air-cooled engines.

Unfortunately, things didn’t work that way in practice.

The Unholy Fail

In the fall 1921, the first Copper-Cooled car was sent to Oakland in Michigan, where it promptly failed all tests. Oakland general manager Fred Hannum delivered the bad news that the Copper-Cooled engine needed more time to cook, six more months of work or more, in fact. At least Oakland had a backup plan to develop a new water-cooled engine while GM figured out why the air-cooled plant sucked so much.

The aftermath wasn’t healthy. Oakland sidelined the air-cooled project for at least 18 more months of water-cooling and Kettering was shaken, but at least he still could still deliver the engine to Chevrolet. Sadly, as MotorTrend reports, Sloan was losing confidence, from MotorTrend:

Sloan, meanwhile, began to express serious misgivings about the program. His issue was not with the technology itself, or Kettering’s ability to deliver it.

“We are not going to get advanced engineering,” he wrote in December 1921, “from a mediocre mind such as the average of our engineers compared with that of Mr. Kettering.” (Ouch!) Rather, Sloan’s concern was with the corporation edging into the divisions’ responsibilities, which was not how the General Motors system was supposed to work.

“We were more committed to a particular engineering design than to the broad aims of the enterprise,” he wrote. “And we were in the situation of supporting a research position against the judgement of the division men who would in the end have to produce and sell the new car.”

Hindsight being perfect, Sloan was probably in the right. However, he was in the minority and the Copper-Cooled project continued with Chevrolet. In March 1922, William S. Knudsen from Ford replaced Zimmerschied and Knudsen was much more enthusiastic about the Copper-Cooled engine than his predecessor.

Still, things got a little weird. Unlike Oakland, which had a backup plan, Chevrolet didn’t. The brand was betting the farm on air-cooling. Even worse was the fact that the Copper-Cooled Chevy was pushed to September 1922. That was just months away, but the car didn’t even exist yet. Thankfully, Chevy eventually decided to produce an updated 490 called the Superior, which would be phased out once the Copper-Cooled engine hit its stride.

Unfortunately, things continued to get worse. Kettering’s team in Dayton failed to produce a prototype and September rolled around without production. Meanwhile, Kettering spent time looking for someone, anyone sympathetic to the air-cooled cause. He eventually landed at Oldsmobile, and by November 1922, the brand was all-in on the air-cooled idea, too. The air-cooled Chevy would come first, followed by an air-cooled Oldsmobile in the summer of 1923.

Finally, the Copper-Cooled Chevrolet, also known as the Chevrolet Series C Copper-Cooled and the Model M Copper-Cooled, landed at the New York auto show in January 1923, going on sale a month later. Chevrolet wanted to kick off production with 1,000 units before gradually increasing production to 50,000 units by October of that year.

The reality was a disaster. Water-cooled Fords and water-cooled Chevys were cashing in record sales but nobody was interested in the Copper-Cooled Chevy.

Then the reviews started pouring in. As Hemmings writes, 150 demonstrator units were built and another 100 found their way into customer hands. It was found that Kettering’s cooling system worked when the car was at high-speed, but was inadequate at low speeds, leading to overheating. The fan was little help. Back then, drivers weren’t taught to speed to cool their cars, anyway. Water-cooled cars cooled down at slow speeds as their cooling systems drew heat away from their engines.

Mac’s Motor City Garage continues with the punches. The Copper-Cooled six was just 134 cubic inches compared to the 170 cubic inch mills found in water-cooled Fords and Chevy’s own water-cooled engines. The air-cooled engine also made just 22 HP, which made it underpowered under even the best conditions. However, when you loaded down the engine, which was pretty much necessary, detonation occurred, lowering output. The overheating at low speeds further nerfed power output. A report in May 1923 indicated that the engines were so fragile that they experienced detonation at moderate speeds and in ambient temperatures of 60 to 70 degrees, a mild summer.

Meanwhile, Oldsmobile was still pro-air-cooled. In anticipation of its own air-cooled cars, it was offloading out-of-production water-cooled cars for a $50 loss per unit. Eventually, the GM Executive Committee had to pump the brakes. The Copper-Cooled program was canceled. Oldsmobile was instructed to build water-cooled cars and those Chevys? They had to go.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Chevy fell well short of its goals. Chevy was supposed to have somewhere around 10,000 cars built when just 759 were constructed, instead. GM began a process of destroying this whole Copper-Cooled thing. There were 239 cars sitting in Chevy’s factory that were scrapped before even seeing a customer’s hand. The 150 demonstrator units were brought back and destroyed. Another 300 cars made it to dealers, of which 100 were in the possession of customers. Chevy recalled all of the Copper-Cooled cars, destroying all of them but two.

Kettering’s baby was destroyed and reportedly, the debacle was bad enough that Kettering volunteered to quit GM. However, he still believed in the engine and thought a new company could have been created to continue development. GM didn’t want Kettering to go that far and instead let him continue his work. Future Copper-Cooled engines were used as stationary Delco generators rather than finding their way into cars. Eventually, Kettering just moved on to something else.

As MotorTrend writes, the Copper-Cooled disaster taught GM:

“[A]bout the value of organized cooperation and coordination in engineering and other matters. It showed the need to make an effective distinction between divisional and corporate functions and engineering … [and] that management needed to subscribe to, and live with, just the kind of firm policies of organization and business that we had been working on.”

As Mac’s Motor City Garage notes, Chevy’s early major blunder had two major factors. One was that Kettering was perhaps so blinded by his obsession that his team declared the Copper-Cooled engines ready for production despite the reports from the fall testing with Oakland. On top of that, Chevy then pushed the engine into production, anyway.

Then there was the engine itself, which didn’t make enough power when it ran right. But that didn’t matter, since driving a Copper-Cooled car on a mild summer day was enough to make the engine fall on its face.

Of course, as we’ve written about a lot, GM didn’t become immune to messing up and the Copper-Cooled saga was just an early screw-up for the company. Thankfully, General Motors never gave up that pioneering spirit. Without it, we wouldn’t have gotten the awesome Chevy Corvair, the Corvette, the Volt, or the Kappa roadsters.

If you’re interested in seeing one of the two surviving Copper-Cooled Chevys, one is at the Henry Ford museum but not currently on display while the other is at the the National Automobile Museum in Reno.

The Nissan Vanette made between 1986 and 1989 (C22 chassis) had to be recalled in its entirety, Nissan had to purchase all of them back and destroy them because they caught fire due to a larger-for-the-US market engine. Some found their way into other countries as used cars and escaped the genocide. We had one for about 10 years, an ’87 model with the 2.4L engine. It was very reliable and we are still alive so perhaps the decision to crush all of them was unjustified?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nissan_Vanette#United_States

The Nissan Vanette made between 1986 and 1989 (C22 chassis) had to be recalled in its entirety, Nissan had to purchase all of them back and destroy them because they caught fire due to a larger-for-the-US market engine. Some found their way into other countries as used cars and escaped the genocide. We had one for about 10 years, an ’87 model with the 2.4L engine. It was very reliable and we are still alive so perhaps the decision to crush all of them was unjustified?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nissan_Vanette#United_States

From an engineering perspective, what caused the engine to not be able to shed enough heat? Was the fan not powerful enough, or were the copper fins not arranged properly to dissipate the heat properly.

Id gander the fan on it and the speed it moved were not enough, as I believe it had the adequate surface area to cool it, another being the type of fan may have played a part in it

From an engineering perspective, what caused the engine to not be able to shed enough heat? Was the fan not powerful enough, or were the copper fins not arranged properly to dissipate the heat properly.

Id gander the fan on it and the speed it moved were not enough, as I believe it had the adequate surface area to cool it, another being the type of fan may have played a part in it

On just one a pedantic note, Charles F. Kettering did NOT invent the cash register, nor, indeed did John Patterson (Founder of NCR). The cash register was invented by James Ritty, a tavern owner in Dayton Ohio who was tired of his cash box being short. He patented it, and Patterson bought the patent and made a MINT. You can still see the bar that Ritty had in one of his later establishments at Jay’s Seafood in Dayton. Cite, I grew up a history nerd in Dayton.

You just added a new layer of appreciation that I have for the bar at Jay’s. Awesome.

On just one a pedantic note, Charles F. Kettering did NOT invent the cash register, nor, indeed did John Patterson (Founder of NCR). The cash register was invented by James Ritty, a tavern owner in Dayton Ohio who was tired of his cash box being short. He patented it, and Patterson bought the patent and made a MINT. You can still see the bar that Ritty had in one of his later establishments at Jay’s Seafood in Dayton. Cite, I grew up a history nerd in Dayton.

You just added a new layer of appreciation that I have for the bar at Jay’s. Awesome.

I think I had that copper cooler on my Pentium 4 gaming build.

I think I had that copper cooler on my Pentium 4 gaming build.

excellent, well written and informative article.

Missing was the method of disposal of returned cars; put on a barge, towed out offshore Lake Erie and pushed-overboard, position unreported.

So water cooled after all.

excellent, well written and informative article.

Missing was the method of disposal of returned cars; put on a barge, towed out offshore Lake Erie and pushed-overboard, position unreported.

So water cooled after all.

Something similar happened with Troller in Brazil. They made a car so incredibly shoddy (the Troller Pantanal) that when Ford do Brasil bought Troller they bought back every single Pantanal (about 81) for any price people asked, just to avoid having to maintain or fix the cars. AFAIK they got almost every single one back and scrapped them.

Troller decided to have a pickup truck and instead of developing a new chassis they just soldered two T4 chassis into one. Not surprisingly, the new Pantanal “chassis” often broke in half.