If you don’t have the cash to finance an entire engineering benchmarking team, it’s rare that you’ll get a look inside every nook and cranny of a production automobile. Thankfully, the experts at Munro & Associates are sharing their deep dive on the Tesla Cybertruck, piece by piece. Today, the team is looking into the hidden secrets of the drive motors themselves.

Our guide for the teardown is Paul Turnbull, lead engineer at Munro & Associates, along with CEO Sandy Munro. As a bonus, this teardown kicks off with an enjoyable disassembly montage. It’s satisfying to see a few impact guns doing the work to disassemble the clean low-mileage motors from the Cyberbeast at Munro & Associates.

Beyond that, it’s a rich tour of the motor technology from a cutting-edge EV. Automakers have wrung a lot of efficiency out of modern motors, and Tesla is up there with the pack.

The Motors, Three

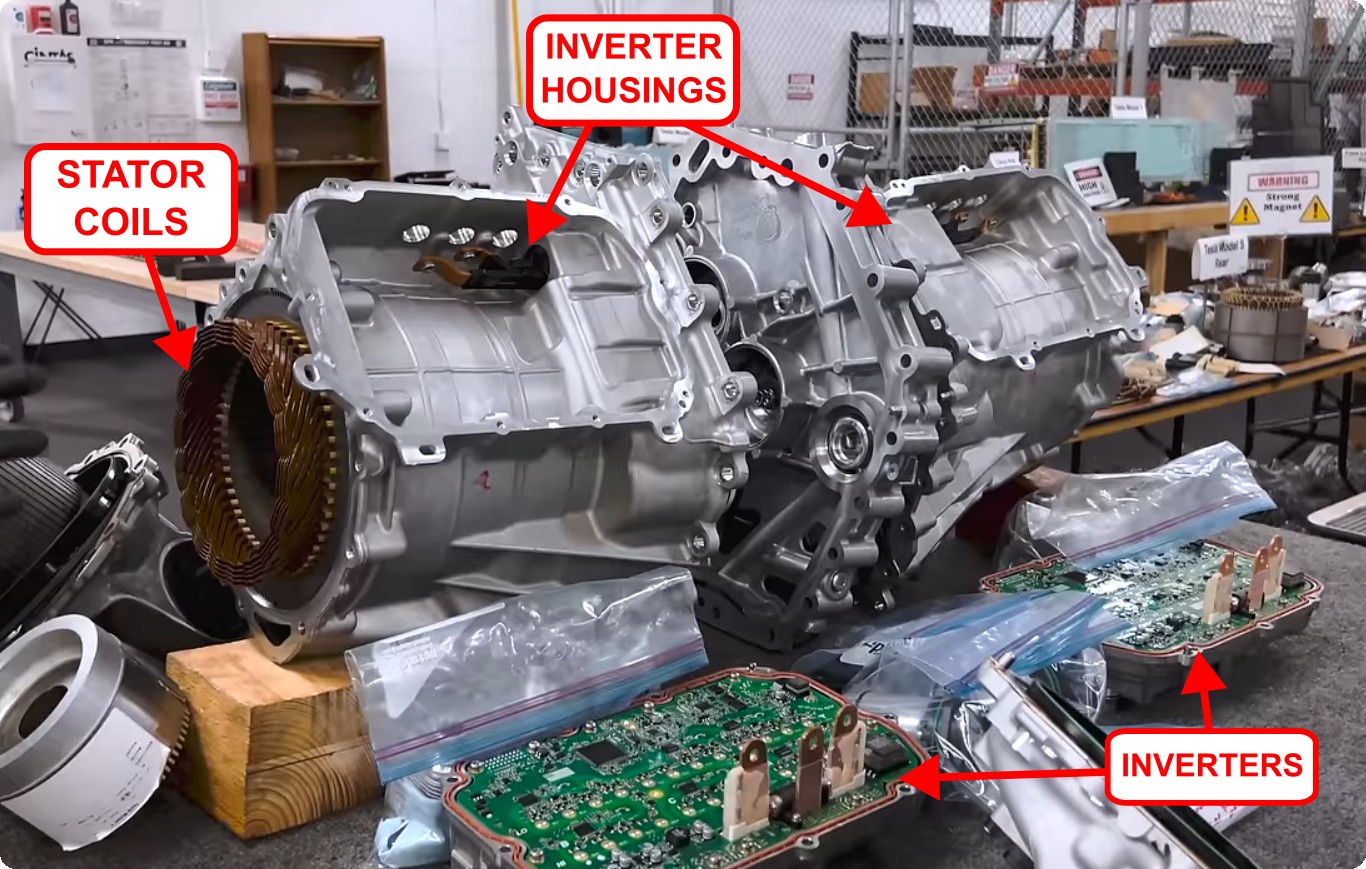

In the top-tier Cyberbeast configuration, the Cybertruck has three motors. Two make up the rear drive unit, while the third drives the front wheels. Total output is a lofty 845 horsepower, which will help the Cybertruck sprint to 60 mph in just 2.6 seconds.

The front drive unit relies on a permanent magnet motor, with a gear mechanism to step down its output for the front wheels. It features an integrated inverter, packaged neatly by the end of the gear mechanism. Turnbull believes this location was probably chosen because it keeps the delicate parts out of the way in the event of a crash.

We also get a good look at the rotor and stator of the permanent magnet motor. The rotor has the magnets, while the stator is made up of neatly stacked hairpin coils. Permanent magnet motors are fairly easy to understand in the abstract. The inverter sends electricity into the coils of the stator, creating a changing magnetic field. This magnetic field is designed to interact with the magnets on the rotor, causing it to spin.

There are two motors in the Cyberbeast’s rear drive unit. It’s a largely symmetrical setup. There’s one motor on each side, with each motor driving a different wheel. The rear motors are induction units, with each of the two motors having their inverters packaged right on the back. Munro believes the cost of the front motor is equivalent to both of the rear motors put together. Much of this is likely due to the cost of the expensive rare-earth magnets in the permanent magnet motor used up front.

If you need a crash course in motor types, induction motors work differently from permanent magnet motors. They pass AC currents through the stator windings which then induce currents in the windings of the rotor. This induced current creates magnetic fields in the rotor which react against the stator’s magnetic field, causing the rotor to spin. The prime difference between induction motors and permanent magnet motors is the source of the rotor’s magnetic field. An induction motor gets a rotor field from induced currents in the rotor’s windings. The latter just has permanent magnets stuck on the rotor instead.

Induction motors have the benefit that they can freewheel with far lower losses than permanent magnet (PM) motors. This is because the rotor in a PM motor always has a strong magnetic field, while the field in an induction motor’s rotor largely diminishes when the stator current is shut down. “It’s a really good arrangement, you can turn those motors off,” says Munro. “You can turn them off, and when you do, they have very low spin loss,” says Turnbull. “On the highway, you really only need 20 to 30 horsepower… the front motor alone can do the job.”

The team highlights that Tesla’s use of induction motors at the rear is quite different from Hyundai’s approach. The Korean automaker often uses multiple permanent magnet motors in its vehicles. To avoid the higher spin losses of leaving the motor connected, Hyundai often fits a disconnect clutch to separate the motor’s drive from the wheels.

The front motor in the Cyberbeast does have an integrated clutch of its own, but for a different reason. It’s to gain a locking differential capability on the front axle. An electromagnet can disengage a clutch, letting the two front wheels rotate independently via differential action. When the electromagnet is disengaged, the clutch locks both front axles together. “[It’s] really handy offroad,” notes Turnbull.

Magnet Story

Notably, we see some damage to the rotor of the front motor, caused during disassembly. The laminations of the rotor are visibly separated.

“One of the functions of this aluminum endplate is to help retain these laminations,” says Turnbull. “With the endplate not coming out to the full diameter, they’ve exposed the magnets, which isn’t a bad thing, but now the laminations are not supported all the way to the outside diameter.”

It appears the magnets may be exposed in this way to open them up for oil cooling. “I think they’re having issues with magnets being a little warmer than they like,” says Turnbull. If magnets get heated to their Curie temperature, they lose their magnetism, so heat management is very important in a permanent magnet motor.

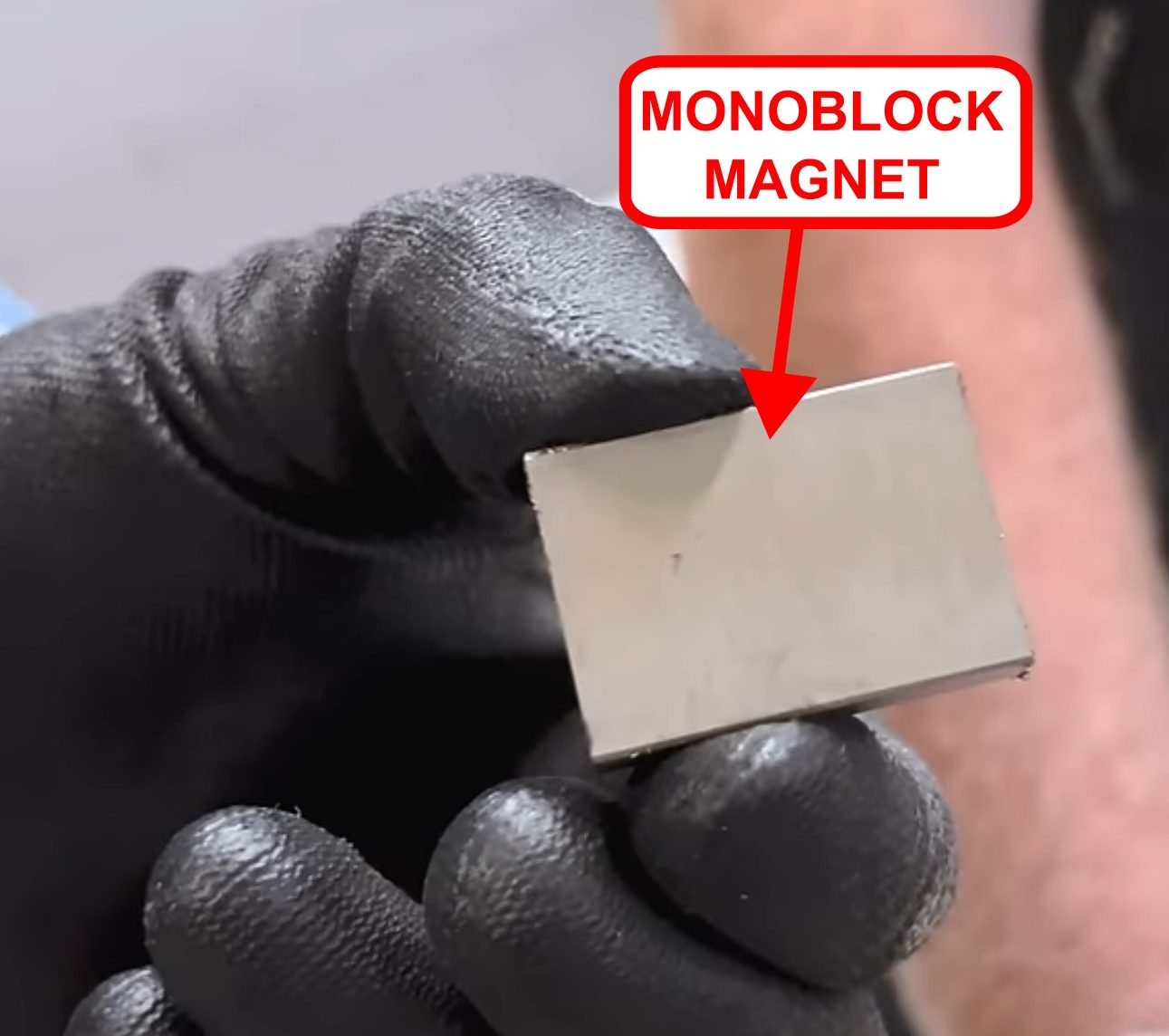

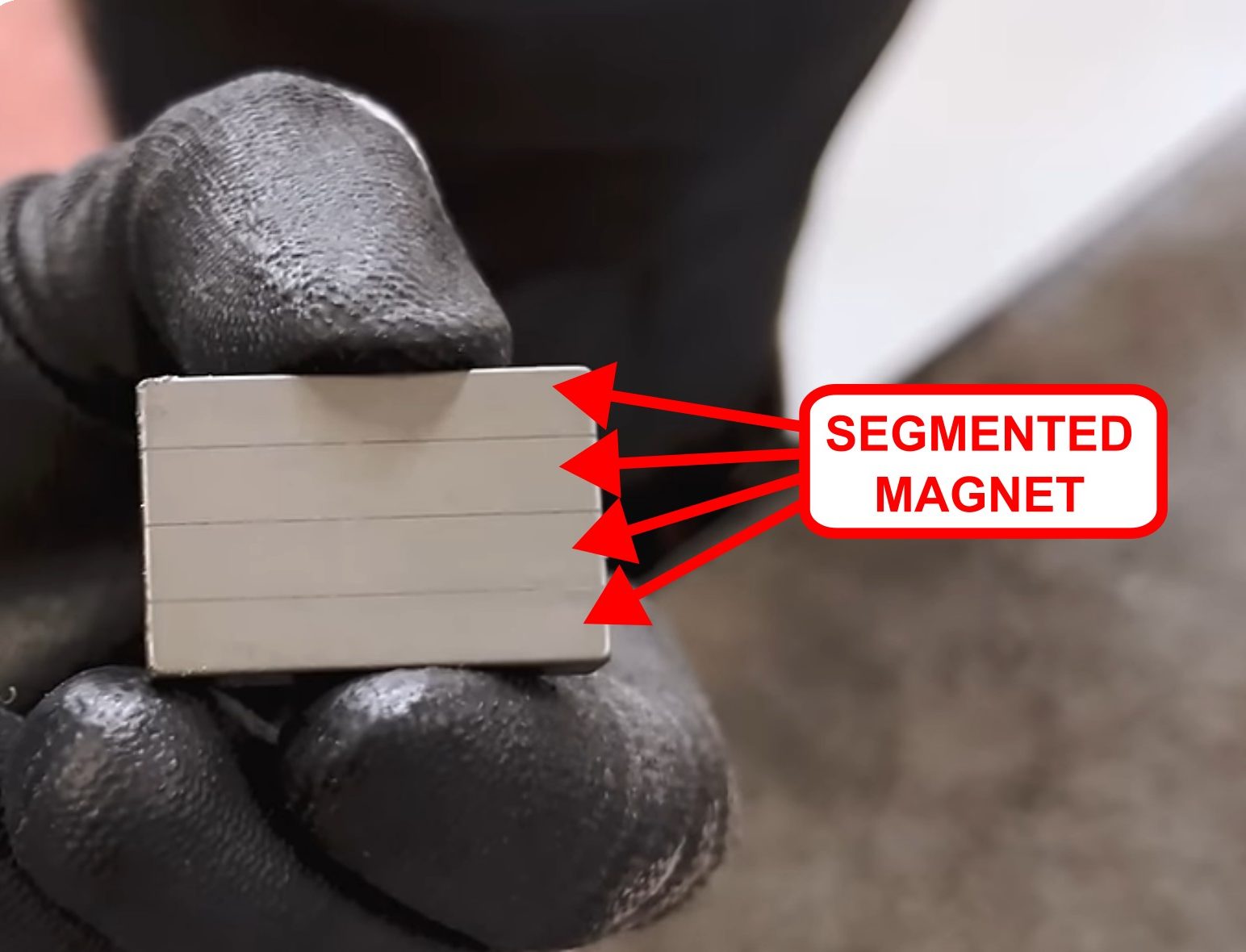

Turnbull suspects cooling could be extra important since the Cybertruck’s front motor relies on monoblock magnets. It’s a departure for Tesla, which had previously pioneered the use of segmented magnets in cars like the Model 3.

A large monoblock magnet is one large conductor, and experiences quite a large eddy current from the moving magnetic fields inside the motor. This eddy current is essentially lost energy that turns heat. However, a stack of smaller individually insulated magnets can generate the same magnetic field while seeing much smaller eddy currents.

It all comes down to size. One large magnet sees a large single eddy current form. Meanwhile, individual magnets in a laminated stack have their own eddy currents which are far smaller. Because the individual magnets are insulated from each other, current cannot easily flow between them. These smaller eddy currents add up to far less than the total eddy current that would flow in a single large magnet. Thus, so-called “magnet losses” are far lower in a motor using segmented magnets. This creates a more efficient motor for better EV range, and one that requires less cooling, too.

“This is one feature that we kind of wish Tesla would go back to—the segmented magnets,” says Turnbull. He notes that while segmented magnets are more expensive in isolation, they can sometimes come out cheaper overall. That’s because a more efficient motor can help an EV can achieve the same range with a smaller battery, cutting costs elsewhere. Munro notes that Tesla pioneered segmented magnets in the Model 3, but has seemingly abandoned them for some of its later vehicles.

Speaking on efficiency, Munro explains that small differences can really add up over a car’s lifetime. “This car’ll probably go half a million, three-quarters of a million miles,” says Munro. “At the end of the day, this little teeny tiny change [to monoblock magnets]… after three-quarters of a million miles, is going to make a huge difference on your pocketbook.” “We’re not here to kiss up continuously,” says Munro. “At the end of the day, what could be better… going back to [segmented magnets] would be one of the things that I would recommend.”

It’s also worth noting that Munro stores loose magnets in a foam block after disassembly. That’s because the rare earth magnets used in EV motors are incredibly strong. Left lying around, they can fly into other magnets or onto ferromagnetic surfaces at great speed. When this happens, they often shatter, causing injury, or they can trap fingers or even limbs depending on size.

Other Highlights

Turnbull also notes there are some smart design decisions in the gearing section of the front drive unit, too. Tesla uses a small notch on some of the large bearings. This notch mates with a pin in the cast housing to hold the outer race from spinning. This allows the bearings to have a slip fit for easy assembly since there doesn’t need to be an interference to hold the outer race in place.

The induction motors are also impressive works of engineering, too. The motor shaft is produced with a “cold-headed” technique. This is where metal is formed at cool temperatures without the addition of heat, using punches and dies to form the material into the desired shape. It’s a process that generates parts with very good strength qualities and a minimum of material waste. The weird surface finish is down to this production method. Cold-headed parts can be made to exacting tolerances, meaning very little machining is needed on the final part.

There are also interesting rectangular channels passing through the center of the rotor of the induction motor. The team believes these are probably for oil cooling the rotor itself, though more analysis is required to confirm the theory.

It’s clear that we’re no longer in the early days of the EV revolution. The Cybertruck, as with many other EVs, has been radically optimized by a company with over a decade of EV experience. It’s nice to see inside the hardware and learn just how far motor technology has come in recent years.

Image credits: Munro Live via YouTube Screenshot, JMAG paper

I could be wrong, but the front motor kinda looks like Tesla’s weird SynRM-IPM design. Which is interesting enough for an article itself, really.

All this discussion on eddy currents in magnets makes this necessary:

https://youtu.be/B9VDoK4UDjI

In the back of my head most of today I’ve been thinking about that last picture. If oil is passing through those holes, how is it being kept from the balance holes and the slots on the outside of the rotor? If either of those are immersed in oil, they would be producing quite a bit of drag—or froth if air is present. I don’t understand how the holes are isolated from the rim and outer diameter.

Anyone see what I mean? Or, am I missing something?

Motor technology is one of Tesla’s strong suits so I’m glad they are still thinking, despite losing it elsewhere

The whole Cybertruck platform is an achievement that’s let down by a bizarre body and some terrible quality issues. Let alone it was released unfinished and not feature complete.

So sad that Elon Musk has apparently totally lost it and gone down this idiotic rabbit hole. So much impressive engineering being wasted though I suppose a lot of this will probably trickle down into their other products.

This is the kind of stuff I love to read. As much as I hate musk and I think the idea of the Cybertruck is stupid, that doesn’t mean all the engineering is dumb and I’d find it interesting either way.

Yeah, very much my take. Nothing is black and white. Even the stupidest cars can have some very interesting engineering in places.

In some ways the cyber truck is so impressive because it’s so ridiculous. The folks engineering this thing were given an insane brief and chasing impossible performance metrics (like the ability to tow “near infinite mass“). Add to that the huge development budget that comes with a Musk vanity project and the end result is some amazing tech.

As a functional vehicle for use in the real world I am not a fan, but as a showcase of what can be achieved with current EV technology it is impressive.

I never tire of the tech stuff and part of it is the fun in speculating why something was done a certain way, what the company was prioritizing, what other options could they have taken, and how those choices might have changed the overall machine, and so on. As much as I hate to admit it in this particular case, it sometimes takes the out-there product idea to result in innovative (or at least interesting) solutions—you won’t see much of that in something like a compact CUV.

Mmmm..delicious. Aluminum-rotor induction motors, though? Wonder why not copper rotor.

Weight and cost I would imagine. The conductivity is lower, but the weight is a lot lower than that (I know it’s a very different application, but when I stopped working on cell towers close to 20 years ago, copper hardlines in some places were starting to be replaced by aluminum to reduce wind-loading and, of course, because it was cheaper). Durability and current capacity is lower, but those can be engineered around (or not!).

Was anyone else here half-expecting to see hamsters?

Thought it’d be rows and rows of tiny Elon Musk clones running on hamster wheels.

*Elon reviews rows of sleepless Musk clones slumped in formation*

“I’ll call them ‘Mini-Me'”

I found this article attractive, it did a good job of driving my curiosity, alternating between praise and criticisms but also being direct with information.

I can rebuild SU carburetors if that helps.

All of my experience with SU carbs comes from small British cars. The juxtaposition of EV tech and British cars in my mind is creating a rift on the space time continuum.

I am newish to the British cars and had to refill my SU dashpots last year. What a weird thing. I have read a couple of articles on them and think I get the concept.

I could have used your help 30 years ago with my ancient 144S and it’s dual SU carbs.

When I first got my Austin Healey, the SU carbs just seemed dumb. Why have this big moving piece that needs lubrication all the time? Then I learned how they work and that the piston with the attached needle valve is a closed loop system that keeps the air/fuel mixture correct for a wide variety of conditions. It really is brilliant and worth the occasional top-up of dashpot oil.

Thanks, Lewin. I deal with AC motors daily* and therefore avidly read anything about both AC & DC motors as there are so many permutations & considerations for different applications that it kinda melts my brain. Plus, magnets are fun—until they’re so powerful they are downright dangerous

*HVAC tech

The oil cooling is suspected? So there wasn’t any in there when it was disassembled?

It’ll drain down in to the sump, and if it’s splash-lubed there might not be any obvious oil feed drillings.

On a daily basis my consideration of magnets seldom extends beyond posting notes on the refrigerator door. Thoroughly enjoyed this dive into the leading edge tech of contemporary electric propulsion motors.

I’m glad! Trying to explain eddy losses hurt my brain.

“It’s got to come out!”

Thanks for hurting your brain in the name of journalism, Lewin.

You did a great job!