My fellow Autopians. Welcome to a new series we are calling Suspension Secrets. In this series, we’ll look at some of the most iconic and influential suspension designs of all time, diving deep into each to show how it works. We’ll start with what is arguably the most influential car ever been produced, the Ford Model T, a spindly-little vehicle that somehow had a suspension known for tackling the harshest of terrains. Here’s how it worked.

Commonly known at the time as the “Flivver” and “Tin Lizzie,” the first Model T was delivered on October 1, 1908, and production continued until May 1927. During that time, over 15 million were built — a production record that stood until the VW Beetle took the title in 1972.

[Ed Note: This is a bit of a dream series for us, and there’s no better person in the world to write it than Huibert Mees, the suspension designer who led the design of the original Tesla Model S, the 2005 Ford GT, and other great cars. He’s written a lot about suspensions for us and will be leading this series. He’s also just a cool guy. – DT]

Here’s Us Breaking Down The Suspension:

Above is the video we made walking through the entire Model T suspension. Please enjoy it, like it, share with it friends, embed it on your websites, comment, et cetera.

Some Background On The Model T Before We Get Nerdy

What made the Model T so successful was a combination of low cost, durability, and simple maintenance. Henry Ford grew up on a farm, and spent much of his time repairing equipment. He valued simplicity, durability and ease of repair, so he wanted to make sure his products embodied those principles. You see this in every aspect of the T, from the design of the engine and transmission to the suspension.

The first Model Ts were built in the Piquet Avenue Plant in Detroit MI. This facility was not capable of building many cars per day, so after producing around 12,000 cars by 1910, production moved to the much larger Highland Park plant where Ford introduced the moving assembly line. While not the first to use this innovation (that distinction belongs to Ransom E. Olds of Oldsmobile fame), Ford refined the system, which led to a steady decline in manufacturing costs, which resulted in a lower price for consumers. At the car’s introduction in 1908, the Roadster cost $825 (equivalent to about $27,000 today). By 1925, the price had dropped to $260 (less than $4,500 today), and Ford was producing around 2 million cars per year.

There is a famous saying attributed to Henry Ford that you could get a Model T in any color you like as long as it is black. While black was indeed the only color you get for a Model T for the majority of production, this wasn’t true for the first few years. In fact, from 1908 through 1913, black wasn’t even a choice! However, to help keep costs down, from 1914 through 1925, all Model T’s were produced in black. Ford bowed to market pressures and began offering other colors again in 1925, although your choice was limited to blue, red, green, or grey.

All of this is to say: The Model T was a no-frills machine that just had to work, even when things got rough.

Two Huge Rigid Triangles Pivot Around A Ball Joint, Let The Model T Flex Like An Off-Roader

So simplicity was the name of the game for the Model T, and this is no more evident than in the design of the suspension. The front and rear suspensions are identical in their concept, and only differ in the fact that the rear has to include a driven axle and driveshaft. (The Model T is rear-wheel drive).

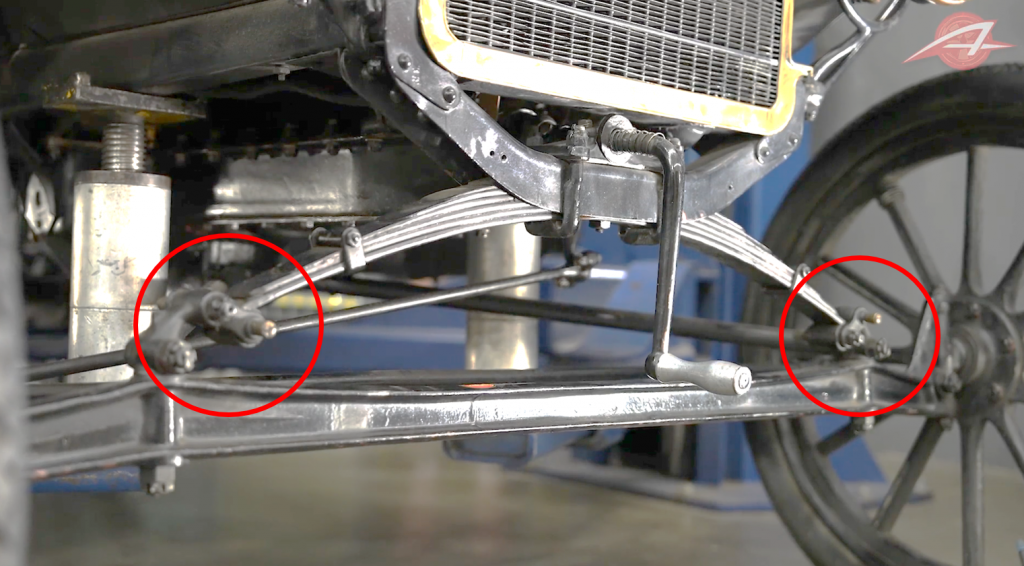

Both suspensions consist of a single triangular-shaped assembly made up of several parts bolted together. The stick axle that the wheels bolt to make up one side of each triangle, while two big metal “radius rods” spanning from the outside of each stick axle inwards make up the other two sides, and meet at a pivoting joint.

There are no upper or lower control arms. No toe links or anti-roll bars. In fact, if you don’t count the springs, that pivoting joint where the two non-axle-sides of the triangle meet is the only place where each suspension attaches to the frame. For the front suspension, this pivot point is a ball and socket, and is located under the oil pan right in front of the transmission:

In the rear, that pivoting point is a spherical housing surrounding the transmission output U-joint.

The stick axles on each suspension are held in place by transverse (i.e. going from right to left) leaf springs that are bolted to the frame and held to each axle with a small shackles at each end:

To help understand how this works, I’ve built a computer model of the rear suspension so we see how it moves up and down and rolls.

Notice how the whole suspension pivots around the ball and socket which is located at the rear of the transmission. This is the only connection to the car. Everything else is controlled by the two shackles linking the axle to the spring (not shown).

Connection to The Car

As with any suspension, how it connects to the rest of the car is critical in the way it functions. As we saw before, in the Model T, this is accomplished with a single attachment in the front and the rear. To give you an idea, here’s a look at a “1940 Ford Axle Set” for sale in eBay, a suspension that’s basically the same as the Model T’s. Here’s the whole front suspension:

And here’s the whole rear suspension:

If you prefer patent drawings, here’s the rear again:

The front attachment is a fairly straightforward ball and socket system with the ball being part of the suspension arms (the two rods) and the socket being a two-piece assembly connected to the bottom of the oilpan. The two pieces are clamped together with a set of springs to keep tension on the ball and take up wear as the car ages (as you can imagine, this ball and socket has lots of grease in it):

Here is what that cap looks like from an early Ford illustration:

And here is what the end of the front suspension arm looks like:

Image via Jalopy Journal

In the rear, however, we have the added complication that not only does the attachment need to connect the suspension to the car, it also has to allow power to pass through to the wheels. It can’t be a simple ball and socket like up front.

The Rear Driveshaft Is In A Rigid Tube

Since the rear suspension has to power the wheels, it needs to include a driveshaft between the engine/transmission and the differential on the rear axle (the back side of the triangle). In the Model T, this driveshaft is housed inside a tube, called a pinion drive shaft housing, which is rigidly connected to the axle:

The rigid connection between the shaft housing and the axle means that i, along with the driveshaft inside the housing, move up and down with the suspension. This means we need to provide some means for the driveshaft to move relative to the transmission. The way this is done on the Model T is with a universal joint inside the ball socket:

This allows the suspension to move up and down and roll while still allowing power to pass to the wheels through the pivot point. Of course, this means the pivot is much larger than the one for the front suspension, but it is a small price to pay to keep such a simple suspension design.

The Steering Gear Was Built Right Into The Top Of The Steering Column

The steering system of the Model T is another area where simplicity ruled the day. Most cars then and now have some sort of a steering box or steering gear, whether it is a rack and pinion or a ball/nut type, but the Model T did not. Instead, what it had was a planetary gear set housed inside a brass canister at the top of the steering column right below the steering wheel:

Inside this canister is a small planetary gearset that provides the gear reduction normally found in a steering box located at the bottom of the steering column:

Image via: Technical – Model T steering question | The H.A.M.B. (jalopyjournal.com)

At the bottom of the steering column is a simple pitman arm (which turns the rotation of the steering shaft into a swinging arc), which is connected to a drag link, which pushes and pulls the right-side suspension knuckle that steers the wheels. A tie rod then connects the right-side knuckle to the left so that when one wheel turns, so does the other.

Let’s see how this system works:

If we open up the steering box, we can see how the planetary gear set works:

Looking at the system from underneath, we can easily see how the motion of the pitman arm is translated into steering of the left and right wheels:

Since the Model T came out, car suspensions have gotten increasingly more complex, and we will be taking a look at some of the most consequential and influential throughout this series. But, sometimes it is refreshing to go back and look at how it all started and how simple things used to be.

Simple, but effective. The Model T put America, and perhaps the entire world, on wheels. It was durable, easy to repair, and could go almost anywhere.

I’ve had a recurring daydream, because of EVs, about how you could make the most mechanically simple car. Like, radically pared back to a near golf cart.

If you used an electrically driven solid axle (ZF makes an integrated motor + axle unit), you could basically use the Model T front suspension on the back and front – because wiring to the back axle takes the place of the drive shaft.

You could fit four wheel drum brakes. With the regen braking possible with EVs, and lower drag inherent in the design, drums are totally viable.

Could you make one light enough to use a manual steering system like the model T? It’s an interesting thought.

We had these same discussions at Tesla in the early days but quickly came to the conclusion that the EV powertrain really doesn’t change the demands on the Chassis. The car still has to handle well, steer well, and stop well. Regen isn’t guaranteed to always be there so the brakes still need to be up to the job and since EV’s tend to be heavy due to the batteries, the brakes have to be good. What WILL change the Chassis is autonomous cars. Everyone loves to drive a Ferrari, but no one loves being a passenger in one, so autonomous cars have to drive like your proverbial grandmother. Steering feel, brake feel, and razor sharp handling just won’t matter anymore.

The brakes need to be good because regen isn’t guaranteed. Good thing drums will stop at least as well as discs for the first stop or two, which is all you should need if you just suffered a major drive systems failure. Limited heat rejection is almost the only drawback of drums. Switching from discs to drums totally makes sense on EVs. At least ones that have no sporting or tracking aspirations, so probably not applicable to the Model S.

This makes me wonder if there could be a market for ‘performance’ autonomous cars that drive like an F1 (or maybe rally?!) driver – instead of being cosseted in comfort, passengers would strap in a five point harness, and then be whisked through traffic at crazy speed while everyone else chugs along safe and comfortable in their Uber bubble.

You sacrifice comfort but if it gets you there faster (and gives you a thrilling ride on the way) some folks might prefer that. Time is money, after all…

Interesting! That makes complete sense.

“You could fit four wheel drum brakes. With the regen braking possible with EVs, and lower drag inherent in the design, drums are totally viable.”

But why would you even want to?

Because drums are pretty much better. They have less drag than discs, lower (unsprung, rotating)weight, lower cost. Longer service life, greatly reduced braking effort.

There’s a bajillion reasons to use drums instead of discs. The advantages of discs? Much better cooling, and a marginally stiffer pedal. If you don’t need the cooling benefit, drums make more sense.

Funny, I’d have expected the opposite.

Drums I think have more mass than discs since they are essentially an unmachined disc rotor with a big lip as the drum. Cooling fins add even more rotating mass, all the way outside. Since I don’t have an example of each in front of me on a scale I can’t say for sure.

Drag? I’m not sure why discs would have more drag since properly set up return springs should keep the pads off the rotor when not engaged, at least as much as drums. I have noted my own discs do seem to have some drag after a change but I always attributed that to needing to be properly broken in.

Lower cost: How so? Drums have more parts, especially the self adjusting types. I have long heard the only reason manufacturers used them so long was industrial inertia. Manufacturers were comfortable with them, the designs were long dialed in, customers didn’t yet care. Drums were good enough, especially for back brakes and they were easier to integrate a parking brake into. Eventually Americans got disc envy from cool European cars.

Longer service life. I’ve never owned a car with front drums so I really can’t say firsthand but I think I’ve changed more rear shoes than pads. I dunno how much if that is due to more modern friction lining.

Why would drums offer less braking force? I’d think that would be a function of friction and leverage more or less independent of whether its being applied to squeezing a rotor or expanding against a drum.

Im no brake design expert so this is all the opinion of a shade tree mechanic. I can say with authority though drawbacks of drums include the drum pistons popping open and wedging the shoes against the drum until they glow red hot. Ask me how I know.

So…..

Drums don’t really seem like they would be lighter, but I saw a guy switching discs to drums on the front of his drag car because, at least for that model, the drum setup was like 10-15lb lighter than the disc setup. Obviously I’m not sure if that’s the case on all cars, but I don’t think it’s usually all that big a difference. Minor benefit.

Drag. Properly set up return springs should do a good job keeping the pads off the rotor, that’s true. But I’ve never worked on discs that had a return spring. I understand they’re fairly common on newer cars, but they are far from universal. Obviously all drums have return springs. The drag is quite minimal even on discs without springs, so this is also a pretty minor benefit.

I don’t entirely understand either why discs would cost more than drums, although I will point out that for my cars, a wheel cylinder and hardware kit adds up to about $30 each side, while new calipers are $100+ per side.

Drums definitely are cheaper, and that is totally the only reason that American cars kept drums. For pretty much the entire 60s and 70s, cars without power brakes had front drums and cars with power brakes had front discs. The price difference was enough that manufacturers thought it was worth it to develop two different front brake setups on most cars.

I’ve never worn out a set of drum brakes, but I’ve never worn out a set of discs either so I can’t really say. A lot of people seem to think that drums last longer, and that makes sense considering there is generally much more pad area, and its protected from grit and water getting in, which seems like would cause extra wear.

Drums require significantly less braking effort than discs, because the rotation of the drum helps drag the front shoe harder against the drum. When the modern incarnation of drum brakes was coming out in the early 50s, there was a lot of marketing showing off “Easy-Stop Self-Activating Brakes”. This is why you will pretty much never see a car without power brakes running disc brakes. This is actually a really big difference, drums need like half as much pedal pressure.

Somewhat connected: drums usually deliver slightly more braking power, because the drum doesn’t need to have a caliper reaching around the outside of it and so the drum can be slightly larger diameter, giving better leverage against the rotation of the wheel.

There is also the benefit of drums staying cleaner and drier just because they’re enclosed. Drums don’t get rusty if you don’t drive your car for a few rainy days.

That’s why I think drums are pretty much better in every way except the major benefit of grossly improved heat rejection from discs.

“This is why you will pretty much never see a car without power brakes running disc brakes.”

My 1960 TR3 and 1981 X-19 beg to differ. The former had OEM front, dual piston discs (first mass prediction car with them!) and standard drums in the rear while the Fiat had discs all around. Neither had a power booster. Neither did my grandmas front disc, rear drum ’82 2101 Lada and I managed to panic stop that thing down from 110 kph, fully loaded with passengers and cargo in my very own moose test without losing control. I even managed to swerve around the car (not an actual moose) that had stopped suddenly ahead of me. Considering that car was built out of repurposed T-34 armor (or at least it weighed like it did) it handled panic stopping surprisingly well. It is true however it was not as good as a late 60s Volvo 142. That thing had amazing power four wheel discs and it could stop on a dime.

“This is actually a really big difference, drums need like half as much pedal pressure.”

Maybe the best way to settle this is to look up old car reviews. Compare cars like the TR2 with non power 4 wheel drum brakes and its successor the nearly identical TR3 with non power front discs, rear drums. Even better look at different trim levels of the same car where one uses discs, the other drums. How did the stopping distance change? Did the reviewer notice an increase in pedal effort? How about performance and gas mileage, any change?

My bad, I’m too used to American cars, extremely few old import cars in Idaho. At least on American cars there is pretty much no thing as unassisted disc brakes, but I’m not surprised that lighter European cars were different.

The main advantages are pedal effort, weight, and cost.

Let me share my personal experience with pedal effort. My 1974 Jeep j10(single cab long bed 6cyl) has no power brakes and drums all around. My 1995 f150(single cab long bed 6cyl) has power brakes and front discs. The j10 only requires a little more effort to stop despite not having power brakes. The f150 stops very very poorly if the engine is not running. I am aware that non assisted brakes often have a smaller diameter master cylinder, but in this case, the J10s pedal really does not have a longer travel than the f150s pedal, so I don’t think there is a large difference in master cylinder diameter.

The outside of drums rusting just doesn’t matter, and can be easily prevented with paint(not really sure why they don’t come painter). The friction surface of discs rusting can absolutely be a problem if it’s bad enough, and I can’t imagine it’s good for pad life ever.

Well it’s no surprise a system designed for power assist performs poorly without it. That’s why I suggested a more apples to apples comparison of different trim levels or model year improvements on the same car. The TR3 was essentially the same car as the unassisted, all drum TR2 but with front discs. I think other European makes had similar vehicles. VW bugs for example.

The outside of drums rusting just doesn’t matter, and can be easily prevented with paint(not really sure why they don’t come painter).

As I mentioned earlier brake drums can get red hot if they’re leaned on enough. I’m aware there are paints that can take it but I don’t think manufacturers want to send their brake drums out to Lockheed’s Skunkworks to get an SR71 paint job…

(Kidding aside 1400F rated BBQ paint would probably be fine)

“There is also the benefit of drums staying cleaner and drier just because they’re enclosed. Drums don’t get rusty if you don’t drive your car for a few rainy days”

That’s not quite true. The inside working surface might not but the exterior sure does. The surfaces on disc rotors get cleaned off the very first time you bring the car to a stop at the end of the driveway. Drums OTOH just get rustier and rustier. Hot drums wet from road splash might even rust faster since the water isn’t being wiped away.

The drums being lighter for the drag car might have been specific to drag needs. That is, a single large brake application. Heat dissipation is sort of irrelevant, so it just needs a big enough thermal mass to absorb the energy without overheating or catching on fire.

Drum brakes heat up faster and start fading much more quickly than disc brakes.

Disc brakes stay cooler longer bc theybhave better airflow and resist fading much longer therefore better braking performance

Which is why I very specifically mentioned much superior heat rejection as the main advantage of disc brakes.

Doesn’t matter for the first hard stop or two, but becomes an issue on long hills or in something resembling sporty driving. This is okay for some vehicles, and not for others.

I really enjoyed this, I had no idea how simple these were.

Relatively light, limited power, brilliant.

Looks like 1200-1600lb depending on bodystyles, year, and options. I’d call that more than relatively light.

Very excellent article and video!

It might be kind of obvious to some but would be good if the article expanded a bit on why this design wasn’t used moving forward, and how/why it compromised ride comfort on general nice(r) roads?

This design was actually used for several decades, all the way through the Model A and Model B.

Hey, I like the new video format. Very nice. And thanks for showing off some of those details in animatics. I’ve got some sweet old pics of family of mine doing some Model T (I think) wheeling back in the day if you want to see https://opposite-lock.com/topic/44163/old-timey-photos

Growing up we had a neighbor that had a Model T.

Likewise there is a family story from the great depression of some relatives traveling from I think Nebraska to other family in Wisconsin and they got something like 11 flats.

Thinking what traveling in the US was like 90 years ago was an entirely different world with paved roads only entirely only existing within city limits and nothing but gravel and dirt roads outside (city limits)

Next time you can discuss split bones and how that affects the T’s suspension geometry

I’ll say it again: The best on road vehicle is the worst off road vehicle and vice versa.

I wonder how different automobiles would be if we didn’t have government owned roads.

Sadly the nature of infrastructure is to built by the lowest bidder, have maintenance deferred for way too long, and some poor schmucks in the future get stuck with the bill to replace it.

Taken to the extreme, tracks and screw tanks are very terrible at operating on pavement. So are steel-tired traction engines.

Some vehicles, like dune buggies and to a lesser extent rock crawlers, can be quite optimized for their off-road environment without necessarily being totally terrible on road.

Well that’s the thing, I didn’t say a world without roads, just without government owned roads. Up until 1916 there was no interstate highway system and we had tons of privately owned roads. With dirt and gravel roads resulting in lower speeds and more rugged terrain I think we’d have modern automobiles that are more like the Model T with tall tires and wheels, lots of articulation, simple, durable, reliable etc.

Nowadays automobiles are being built as if we had perfect glass smooth roads while in reality our infrastructure is crumbling and our automobiles are getting more and more disposable while prices keep going up.

I was just agreeing with your statement that the best vehicles off-road are the worst vehicles on road

Ah, my bad.

“I wonder how different automobiles would be if we didn’t have government owned roads.”

It wouldn’t matter much as you’d be constantly paying so many tolls you’d never get anywhere or have any money left.

Then how do you explain roads in the US prior to 1916?

Lower population so fewer people to be toll booth operators. Automatic collection wasn’t reliable enough. No video cameras to catch and prosecute toll violators. The costs and hassle would have outweighed the revenue. Times have changed.

I’ll say it again: The best on road vehicle is the worst off road vehicle and vice versa.

So where do hovercraft fit into that? They do just as well on smooth roads as they do on a smooth lake as on a smooth mud pit. Not many other vehicles can make that claim.

Super interesting. Looking forward to more of this series

Great article, Huibert and David! Thank you! I learned a lot about something I had never looked into.

Given the engineering and manufacturing capabilities of 100+ years ago, and the (lack) of roads these vehicles had to navigate, I believe the Model T suspension is an elegant design. Different in how we refer to an elegant design in modern vehicles, yet elegant in its ingenuity, simplicity, functionality, manufacturability, and service & reparability.

On a side note, a friend in high school lived on a farm and had a 1928 Model A that was all original and had been in the family since new. It always amazed me where that car could go, through steep hilly woods, mud, sand, two-tracks, no-tracks, pastures, and never get stuck.

I have a friend who has one. It’s closer to a tractor than a car really.

Speaking of “agricultural” driving experiences, here’s hoping we can have a deep dive into the Land Rover coil-spring/solid axle suspension of the original Range Rover, and later the Discovery and Defender. Having owned a Disco 1 and a project Rangie, their suspension design is remarkably good off-road, and still manages to be quite comfortable and well-behaved on-road at speed.

I think the Range Rover is a completely conventional four link and coil springs solid axle front. The same as most Jeeps, most new 3/4 ton pickups, some of which are very luxury and ride very nice, and used on the rear suspension of many vehicles. I think they already did a pretty deep dive into links vs coils in the Ranger article.

Excellent article!

I’ve looked at Model Ts more times than I can count, but always figured much less thought went into the suspension design than was actually true.

I hope Classic Mini rubber cone suspension gets an episode.

Citroen oleopneumatic, too!

We certainly do not need the torsion bars used by VW and Mopar explained because Jason.

…or by Nissan pickups from the 60s through the 00s.

2CV next!

It’s on the list!

Looking forward to the rest of the series.

Spherical ball joint all the things! Great article and I am psyched about the rest of the series. My suspension knowledge is weak and I am looking forward all that new stuff to geek out over.

Also, that steering reduction gear is a great detail to point out. I know I’ve seen that brass housing under a Model T steering wheel any number of times and never even suspected what it was hiding.

A guy at a previous company I worked at used to daily drive his Model T. He said with 15+ million made, parts are still very available and cheap.

How fast can you go in one of these before the dynamic behavior becomes truly frightening? (yeah, I understand that the Model T is all about simplicity, durability, go-anywhere capability, etc)

There don’t appear to be any shock absorbers in that suspension do there…

That may be less of an issue than you imagine. Many heavy trucks into the 80s did not always come equipped with shock absorbers. Heavy trucks still have shocks that are extremely undersized for the size of the vehicle compared to what you’d expect from a car.

Just the friction in a leaf spring, especially one with many leaves, has a significant shock absorber effect.

That is fascinating. I figured the friction between the leaf spring leaves would have some damping effect, but I never would have guessed it was substantial enough to negate the need for dedicated dampers to that degree.

It depends to a large degree on how many leaves the spring has, and how crusty and rusty the spring is. I think reduced friction damping is part of the reason that cars have so many less leaves than they did, with many springs having one, two, or three leaves.

On cars from the 20s and 30s, especially fancy ones, it was not uncommon to have a leather boot sewn to closely fit the leaf spring, and you would pack the spring and boot with grease for a friction free spring and an ultra smooth ride.

40-45 mph is about the limit but this same suspension was used in the Model A and Model B and many race cars were built off of those cars. Only small modifications were made to the suspension to make it work in those cars.

And there was a whole industry of aftermarket go-fast parts for Model Ts, higher compression cylinder heads, overdrive units, new exhaust manifolds. Wasn’t impossible for a heavily modded one to hit or exceed 60mph, especially with one of the lighter weight body styles, like the runabout.

My uncle claimed vociferously that he got one of his father’s up to almost 55. It did have a later engine, so was possible.

He was quite emphatic that it was a damn fool thing to do & that he never exceeded 45 in one after that.

There’s a car museum in Oregon where they teach you to drive model T’s: https://waaamuseum.org/education/model-t-driving-school

There is in the UK car dealership that also gives model T driving lessons and more

https://www.modeltford.co.uk

They are very charming folk and the pub is pretty good as well.

The biggest challenge with driving the Model T is the transmission. It uses pedals instead of a gearshift.

Came here to say this, and they still have spots open for this year!

The museum is just outside Hood River, about an hour east of Portland up the Columbia Gorge.

The Gilmore in Michigan does it too. https://gilmorecarmuseum.org/learn/model-t-driving-experience. The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn used to offer it occasionally. You can go for a ride in one of their many Model T’s in Greenfield Village whenever it’s open. A few of the Detroit Autopian group did Model T rides this summer.

Great article!

I really am not familiar with Model Ts, which is a sorry state of affairs. I would love to see more Model T technical articles on The Autopian. Looking forward to more Suspension Secrets articles.

I had no idea that Model Ts used this kind of suspension link! I was already familiar with this, because this is what is referred to on Pirate 4×4 as a “grader ball” suspension. This is because that one ball joint needs to be a very large and strong one, and the traditional way of sourcing such a ball joint is to go to your local CAT equipment dealer and buy the humongous ball joint that holds the blade onto a road grader. Some people have also used a trailer tongue and hitch ball, which is really redneck but I bet it would totally work, and it’s sure strong.

Transverse leaf springs are a great idea with this suspension geometry, and eliminates the need for a track bar. Honestly, that would apply to a normal four link suspension geometry too….. Hmm……. I’m guessing the reason nobody has made a four link with transverse leaf spring is just for packaging, because that’s necessarily taller than a track bar and coil springs. Which is especially an issue on the front suspension and oil pan clearance.

Fun fact: The overwhelming Majority of Model Ts use Thermosyphon cooling systems. No water pump!

I did actually know that. And cars that do come with a water pump usually use a reverse flow cooling system: cool water enters the top of the engine and hot water exits the bottom, while hot water enters the bottom of the radiator and cooling water exits the top. This being opposite from the direction that convection would want water to flow, and that it does flow on thermosiphon cooling systems.

This is excellent Autopian. Thanks David and Huibert.

I have to admit that’s my favorite tire tread pattern:

https://live.staticflickr.com/7014/6835441823_44be2cef93.jpg

That is amazing. Now I want all terrain tires that say ALL TERRAIN or A/T or SWAMPERS or something in the tread.

Me too. I always suspected that they were better at marketing than roadholding but my Dad has those on his antique car and they work fine.

I know David Byrne is a polymath, but I didn’t expect him on the Autopian!

And you might find him behind the wheel of a large automobile…

Just great, great stuff!

Looking forward to the next episode already!

I never knew about the planetary up there either—or questioned the casing there despite having spent a fair few hours in them over the years.

my inner nerd thanks you warmly, Mr Mees!

You’re very welcome! Stay tuned for more nerdy stuff.

Well I’ll be damned. I knew how the suspension was set up, but I had no idea about the planetary reduction in the steering wheel hub. I learned something today!

This is a fantastic article

I beleive Henry FOrd was quoted “the driver is the shock absorber”