The first generation Ford Mustang was the start of one of the most iconic nameplates in automotive history. Introduced part way through the 1964 model year as a 1965 model, the Mustang quickly became a top seller for Ford. During its first half year of production in 1964, Ford sold over 121,000 Mustangs followed by almost 560,000 in 1965. The model was so successful, in fact, that it spawned an entire new class of cars called “Pony cars.” Both Chrysler and GM would follow in 1966 and 1967 respectively with their own pony cars – the Dodge Charger and the Chevrolet Camaro/Pontiac Firebird. But the Mustang would remain a sales king for many years to come; in fact, it’s still the King of the Hill among sport coupes. Given the Mustang’s status in auto history, it only made sense for us to include it in Suspension Secrets, our regular deep-dive into the suspensions of some of the world’s most iconic cars. Let’s get into it.

Baby Boomers

The Mustang was developed in the early ’60’s as a result of Lee Iacocca, then Vice President and General Manager of Ford, wanting to tap into the baby boomers who were coming of age. Many were college educated, and Ford’s research showed that these customers bought cars at a much higher rate than others, and they wanted something fun and sporty. Still, Boomers weren’t flush with cash, so the car had to be reasonably priced. This meant keeping costs down and using as many existing parts as possible.

The team quickly determined that the unibody Falcon, a small coupe (though it could be had as a sedan or wagon, too) would be the right car to start from. It was a fairly new platform, was the right size, and could accommodate the desired engine choices. The resulting Mustang was a vehicle that had a very common suspension layout for the time with a solid rear axle and a double wishbone in the front.

Double Wishbone Front

While the front suspension can definitely be called a double wishbone, there are some aspects of it that are quite unique.

The lower wishbone is not really a wishbone, as such, but is actually made of two parts – the lower arm and a strut. The parts are held together with two bolts, and are connected to the body with rubber isolators and bushings. Since the connection between the two components is rigid, the arm and strut work together to act like a wishbone.

The upper arm looks much more like a traditional wishbone, but that’s where the similarities end. The connection between each arm and the body is via two metal-to-metal pivots. There are no rubber bushings here. These pivots must be regularly greased to keep them from wearing out and do little to isolate the car from road noise and impact harshness. These early Mustangs were not cushy or quiet.

The other aspect of the upper arms that is unusual is a result of how the spring is mounted.

Spring Mounting

Traditionally, even in the early sixties, the springs in a double wishbone suspension would be attached to the lower arm either by sitting on the arm directly, or as part of a spring/damper strut assembly.

Here you see a 1965 Ford Galaxie 500 front suspension with a very similar lower arm and strut arrangement as the Mustang has but the spring is sitting on the lower arm.

In the Mustang, however, the spring is mounted on the upper arm and sits on a small pivot so the spring doesn’t have to bow as the arm swings up and down. This explains why Ford used metal to metal pivots instead of bushings in the upper arm. The pressure of the spring would be too great for the rubber to handle, and they wouldn’t last very long.

I don’t know why Ford put the spring on the upper arm like this, but I did hear an interesting story many years ago. According to legend, the Falcon platform was originally developed to be front wheel drive, but this was changed over the years until it finally entered production as rear wheel drive. By the time the decision was made to ditch front wheel drive, the design had already matured with the spring on the upper arm in order to keep it out of the way of a driveshaft. I don’t know if this story is true but looking at the design, it does make some sense. If anyone knows more about this, I would love to hear about it.

‘Hotchkiss’ Rear Suspension

The rear suspension in the Mustang is a much more traditional design found in many cars of that era. It uses a solid axle held on by two leaf springs. Known as a Hotchkiss suspension, it is a very simple design still used in many pickup trucks today as well as in plenty of pre-2000 Jeeps.

There are no links or control arms in a Hotchkiss suspension, the leaf springs do it all. They hold the axle in place, keep it located fore and aft as well a side to side, and they act as the springs by flexing up and down.

The big difference between a modern pickup truck Hotchkiss and the one in the 1966 Mustang is the location of the dampers. In the Mustang the left and right dampers are both attached to the front side of the axle while in a modern truck setup one will be mounted on the front side while the other on the back side of the axle. This is called a staggered shock arrangement, and it is done to combat axle hop.

As you apply forward engine torque to a Hotchkiss suspension, the wheels will of course want to rotate in the forward direction. At the same time, the axle housing itself will want to rotate in a rearward direction as a reaction to that torque. Since the only thing holding the axle in place are the two leaf springs and since these springs are relatively flexible, the reaction torque forces them into an “S” shape.

This is called axle wind-up. If the tires stay hooked up to the pavement while this is happening, all will be fine, but if you have a lot of engine torque or if the road is a bit slippery from rain or leaves, then the tires may lose traction. When they do, the springs will snap back to being straight. When the tires regain traction, the whole process starts over again. In bad cases, this cycle can happen several times per second and cause a violent shaking in the car.

If the dampers are both mounted either on the front or back side of the axle, the axle rotation during wind-up happens along a line between the bottoms of the two dampers. If, on the other hand, we place one damper in front of the axle and the other behind, the wind-up would force one or both dampers to stroke which would add damping to the wind-up and help stop it.

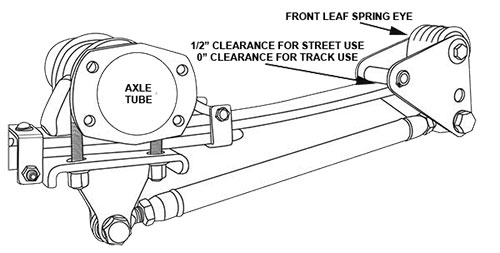

In 1965, this problem wasn’t such a big deal since engines weren’t yet very powerful but as engines got bigger and stronger, especially in cars like the Mustang, axle hop became a much bigger problem. Hot rodders of the day quickly learned to use traction bars like these:

…to help stop the wind-up and the resulting axle hop.

Ford stuck with the Falcon platform for the Mustang until the Mustang II arrived in 1974, racking up several million in sales in the process. In spite of some of the issues this platform had, there is no arguing that this represents a supremely successful design which is still revered today.

As someone who recently inherited a ’65 convertible GT-clone – and is starting to look critically at a 60-year-old suspension and making a list of what I should probably be replacing – this was both timely and appreciated. I do wonder how much ‘fun’ I’ll face when it comes time to have all this aligned…

Thank you. After chewing on this a little, it really goes a long way to explaining the rest of the… peculiar… handling characteristics of the ’66 convertible I used to own. The snap oversteer isn’t entirely attributable to a twisting unibody (though it somewhat is).

Oh so that’s what traction bars do.

Great article Huibert! I see in the comments that you are taking suggestions for cars to feature.

I nominate the 2cv. A colleague of my wife has one and that was the first time I looked under that car. The suspension design is really unique, I’d love to know more about it!

I agree,the 2cv would interesting to read more about.

Did mounting the axle behind the center of the leafs really do much to reduce windup on the Mopars?

The lower “wishbone” made from two radius arms is EXACTLY how it works on 1990-1993 Accords, of which I have two. I mean exactly, down to the two bolts rigidly connecting the two radius arms together, and the style of bushings. Not sure if other Accords use this setup, but I know Civics don’t.

I love suspension tech.

I think it’s because you can look at a suspension component and move it around and immediately sort of comprehend how it works.

As an Australian it’s funny that this front suspension is considered a bit odd – this design was used in Aussie Fords up until the 90s, so I bet a lot of us would think it’s perfectly normal and boring!

The article does solve young me’s confusion at why diagrams of common front suspension types didn’t have any that seemed to match the Falcon’s, mind

And that would make sense. The original Australian Falcon was just a locally produced US Ford Falcon. They would have had the same “odd” suspension design. As the Falcon diverged and became it’s own thing in Australia, it continued to use this “odd” design which was more common in Australia.

A well off Uncle traded his Lincoln for two fully loaded Gen One Mustangs. Apparently they went out of alignment at the drop of a pothole.

As for axle hop, that’s demonstrated in “Bullitt” when Steve McQueen backs up after a slide out.

There is a mistake in the article. Hot rodders of the day would have used a slapper bar on the rear springs. A slapper bar is basically a piece of square tubing attached to the lower spring plate with a rubber snubber under the front spring eye. The pictures are of a cal trac bar which is a modern invention.

Wow, that’s a flashback to high school! All the cool bad ass cars had names airbrushed on the back…

Yeah, I was hoping to show slapper bars but couldn’t find a good picture we could use.

That’s not quite correct. While many hot rodders surely used slapper bars and CalTracs came out in the 90s, Shelby added under-rider-style traction link bars to the first GT-350 in 1965 and TractionMaster (the OG supplier for Shelby, I believe) has been making them for leaf spring cars since the 50s. The traction bars are 100% required because you can’t launch a stock Mustang for shit without axle tramp trying to bounce you across the street and pound the car into pieces.

These were link bars that bolted to the spring perch and the other joint was welded to the subframe in front of the axle, not “slapper” bars. I have a set on my 1966 Fairlane and they work great! I couldn’t launch the car or spin the tires at all before I installed them without massive, destructive axle tramp, even though I had new 5-leaf springs and good shocks.

Excellent, I’m working on a 69 Mustang right now, and now I know where to get some traction bars.

Another method used in the 60s and 70s (particularly on Chrysler vehicles, but also on Fox body Mustangs) is the pinion snubber, which is a rubber snubber on the pinion of the rear end, which hits the floorboard of the car if the axle rotates too much.

CalTracs are great too and don’t require welding, but they are significantly more expensive than the TractionMaster under-riders.

Significantly!

On my leaf spring Nova, as the power increased it progressed from slapper bars though an adjustable pinion snubber when I went to Chrysler rear and eventually to ladder bars with leaf spring sliders and axle pivots. The car went from streetable to drag race only. If I was to do it again I’d go 4 link with a track bar and coil overs.

1970 to 1977 Maverick and 1975 to 1980 (U.S.) Granada used this platform as well.

OMG please continue injecting this pure, unadulterated nerdy tech talk straight into my brain.

It really looks like a front suspension waiting for a half shaft. (-;

“Both Chrysler and GM would follow in 1966 and 1967 respectively with their own pony cars – the Dodge Charger and the Chevrolet Camaro/Pontiac Firebird. ”

Err, I think most people would agree that the Charger was a muscle car, not a pony car. Chrysler’s pony would have been the Plymouth Barracuda, which actually came out just before the Mustang.

Came here to say this. Sadly, despite being introduced 16 days before the Mustang, the Barracuda was far less popular, else we might otherwise refer to that automotive class as “fish cars.” And you have to admit that would have been much more fun to say and write.

I will prompt ChatGPT to write a fanfiction about the automotive landscape if “fish cars” became a thing.

After this baited hook I’m waiting with bated breath.

And I’m quite curious about what ChatGPT might spawn.

It did, briefly. *cough* AMC Marlin *cough*

Wanted to point this out as well. “Pony” cars were based on a compact platform with a much sportier body on it. Mustang sprung from Falcon, original Baraccuda sprung from the Valiant, and the Camaro sprung somewhat from the Nova.

The original Charger was the same concept, but on the larger B-Body platform. The original Charger could be considered one of the original PLC Personal Luxury Coupes, because the original Charger was a much more luxurious offering than what was to be the 2nd generation Charger.

My memory from the 70’s is you could hear an early Mustang’s suspension squeaking well before the car came into view.

Yes, very common to have holes torched into the shock towers so could add zerks so you could grease them….was pretty embarrassing to be driving the squeaking Ford in high school… 77 Maverick with 302 in my case .

Yup! Ford saw fit to install grease fittings facing the walls of the shock towers so there was no way to attach a grease gun. Real smart!

Ford actually installed plugs in those holes and for the first service you had to remove the plugs and insert Zerk fittings. Note plugs from the factory in bushings, ball joints and tie rod ends was pretty common and it was always interesting to see several year old car come in with the plugs still in place.

You’re lucky to have survived. A friend of mine had one of those and was killed in it when the front suspension sheered off because the guy he hired to rebuild it to fix the squeek did so with regular hardware from true value rather than grade 8 stuff.

I never really thought about the 65-69 Mustang’s suspension; to the extent I thought about it at all, it was the Fox-body Mustang’s front suspension using struts with springs mounted inboard of the strut body rather than over it. I don’t know why they did this so all I can do is look at one and guess. Putting the spring inboard means a stiffer spring rate for a given wheel rate, which means a smaller, taller or both spring. What advantage would this give? Perhaps it lets you package the strut housing further out for a smaller scrub radius without the package interfering with the wheel and tire? But the strut tops on later Mustangs don’t seem particularly outboard. I’ve never thought deeply about it so I’m just thinking out loud now.

There is a theoretical advantage that you can have a lower hoodline with that spring arrangement but honestly, I think it was a mistake. The engines they used still required a high hood so they were never able to take advantage of it. Unfortunately, taking the spring off the strut meant they couldn’t use the spring force to counteract the sideforce on the shock so there is a LOT of friction in those suspensions. Why Your Front Suspension Was Designed To Have A Spring And Shock Just Barely Out Of Alignment – The Autopian

…which is why there seem to be plenty of aftermarket suspension options for 65-70 Mustangs that convert it to an SLA setup, which generally has better camber gain than a strut. And moving the strut top out would make that worse, not better. Putting the spring inboard limits what engines will fit in there, but I can’t imagine that was an issue when the chasis was designed, since it was designe for the Falcon and straight sixes, and once they put V8s in them the 260289/302 fit anyway. Perhaps they just wanted to distribute the loads on the front of the body? ????♂️

I enjoy your chassis & suspension articles – when I was in engineering school I focused on ergonomics and composites, but I’ve always really enjoyed vehicle dynamics and suspension design.

Chevrolet copied that same front suspension design on the 1962 Chevy II/Nova thru 1967. The Mustang II (actually Pinto) suspension become the basis for the aftermarket for streetrods.

Prior to the Pinto the Corvair front end filled that spot.

Ramblers/AMCs also used springs on the upper control arm.

Great info as always – thank you Huibert!

I own an ’02, and I think (but not sure) by then Ford had long since gone to a staggered shock arrangement, right?

I ask as interestingly, it has an extra set of horizontally-mounted dampers (Ford called it “quadrashock” IIRC) to help with wheel hop, so maybe it’s not staggered?

I’m almost certain they are not staggered on my 95, I changed them a while ago and fairly certain the are both in the same location/angle and came out through the trunk

Thanks…then they’re not on mine, as Ford wouldn’t have changed anything on the SN95 at that point.

I need to change mine soon too.

My memory was a little off, they don’t come out through the trunk, but the top nut is accessed from the trunk, then unbolt the bottom and pull them out from below.

like anything mustang related, there’s about a dozen youtube videos on it.

I appreciate your jogging my memory to do it. What shocks did you use/do you like them?

I can’t remember, it was about 4 years ago, probably something midgrade from rock auto, couldn’t even find the receipt. The cars stock so I can’t imagine I went too high end. It did improve the ride compared to the 25 year old factory ones but that’s not saying much

I’m sure I’ve gotten used to mine being worn, so I’m looking forward to what new ones will feel like!

The shocks on your ’02 are NOT staggered but that’s OK since you don’t have a Hotchkiss suspension either. You have a 4 link which controls axle windup through the links. You are also correct when you say you have Quadshocks. Those are the two small horizontally mounted shocks you see behind the axle. These are there because even though you have 4 links, they are mounted in rubber bushings that are there for comfort and road noise isolation but also still allow some axle wind-up. The Quadshocks help stop that.

Thanks Huibert!

I’d read that the Mustang’s biggest problem over the years was never the power; it was getting it to the pavement. I enjoy how the SN95 was still working on that. Ford seems to have solved it now though.

They are not staggered on the 8.8 used from 79-04. It did utilize a quad-shock with two additional smaller shocks placed on the top/out front but they are considered useless by most and a lot believe they actually make traction worse so it is very common to see them removed. I have and like the Bilsteins. Even once I switched to the IRS I still made sure to get them. I also installed them on my brothers 04. That is if you’re lowered. If you are stock height or pretty close to it there are cheaper options that are fine. Also another tip for you, if you are slightly lowered from factory and want to save money the Foxbody shocks are a direct swap and are an inch or so shorter so you can save money and still have good ride quality.

https://lmr.com/item/BIL-35041382B-K/bilstein-mustang-b6-series-shock-strut-kit-94-04

I remember you mentioning the Bilstein quality before, but I’m esp. grateful now for the Fox-spec tip – I’d heard that, but was hesitant to pull the trigger without some more knowledgeable input!

I’m running the kinda unusual FRPP B-springs (progressives) on mine. I know the Cs were popular, but after riding in a Mustang with them, the road-racer stiff feel wasn’t really what I wanted. They lower her less than an inch, just enough to get rid of that odd high-riding look.

What’s funny is that my first New Edge had Ford Racing B springs on it when I purchased it. Although I swapped them out for H&R SS springs almost immediately. But I am also just a fan of lowering my cars to the edge of functionality as a general lifestyle haha. My Mach 1 is low enough that I had to raise the coilovers a 1/4″ because my headers occasionally lightly touched the road on heavy bumps.

With that height, the Fox shocks should be perfect. The Foxbodys use the exact same lower control arms and rear mounts. Of course, New Edges are still on the Fox platform so that makes sense. Specifically the Fox4.

Great info on axle hop. I have a 65 with 500 hp and leaf springs, far from ideal. Wheel hop is really violent, even with under rider bars.

Love your articles, Huibert.

I didn’t know that the coil sat above the upper control arm on the OG Mustang, like an AMC Eagle (which clearly came much later).

From your EXTENSIVE experience with suspension/chassis design, I’d love to hear your take on the bizarre 1955-1956 Packard Torsion-Level Suspension.

I absolutely adore that Packard suspension!! It’s so cool and innovative. I’ll add it to the list of cars to feature, if I can find one.

I think it’s SUPER cool as well. So interesting I wonder why a (very updated) version hasn’t really been tried utilizing torsion springs and motors to load/unload. Especially given the popularity of adjustable suspensions today.

Looking forward to that piece in the future 🙂

The problem is that the system used torsion bars that went from the front suspension all the way to the rear suspension. In modern cars there is simply not enough room under the floor to package them.

Good point!

My father collected Packards so I got to experience the Caribbean suspension many years ago. Even as a kid I was impressed.

While the AMC Eagle did come out far later than the Mustang, AMC had been using the same basic suspension design with the spring mounted on top since the 50’s with the Rambler.

Great article! But get some new tires, those are shot.

Yeah, that’s David’s car and he knows. Also, the alignment was way off in the weeds somewhere. We drove it from his house to the shop and it was…….an experience.

David being David, this is probably exactly how he drove it across most of the country.

My lips are sealed.

I’m glad someone got to this before me, but those tires are scary.

Many shops uses the old book values for angles, but don’t realize that’s for bias ply.

Radials need different values, or you get wear patterns like that.

That and probably has worn out bushings and ball joints, that makes the original 50 year old settings even worse.