I have miraculously stumbled upon priceless relics of automotive history: the factory service manuals for the General Motors EV1, the legendary electric car so far ahead of its time that GM had to take every one back from celebrity owners like Mel Gibson and Baywatch actress Alexandra Paul, and crush it. The drama surrounding the destruction of this beloved vehicle — the very first purpose-built, commercially-viable electric car — cannot be understated, with a multi-week vigil attended by numerous celebrities, and a famous film called “Who Killed The Electric Car?” Everyone loved the EV1 because it was incredibly innovative, and there’s no better way to get a glimpse of these revolutionary innovations than to look through these priceless service manuals I now have in my possession. Get ready to have your minds blown.

Some Background On The GM EV1

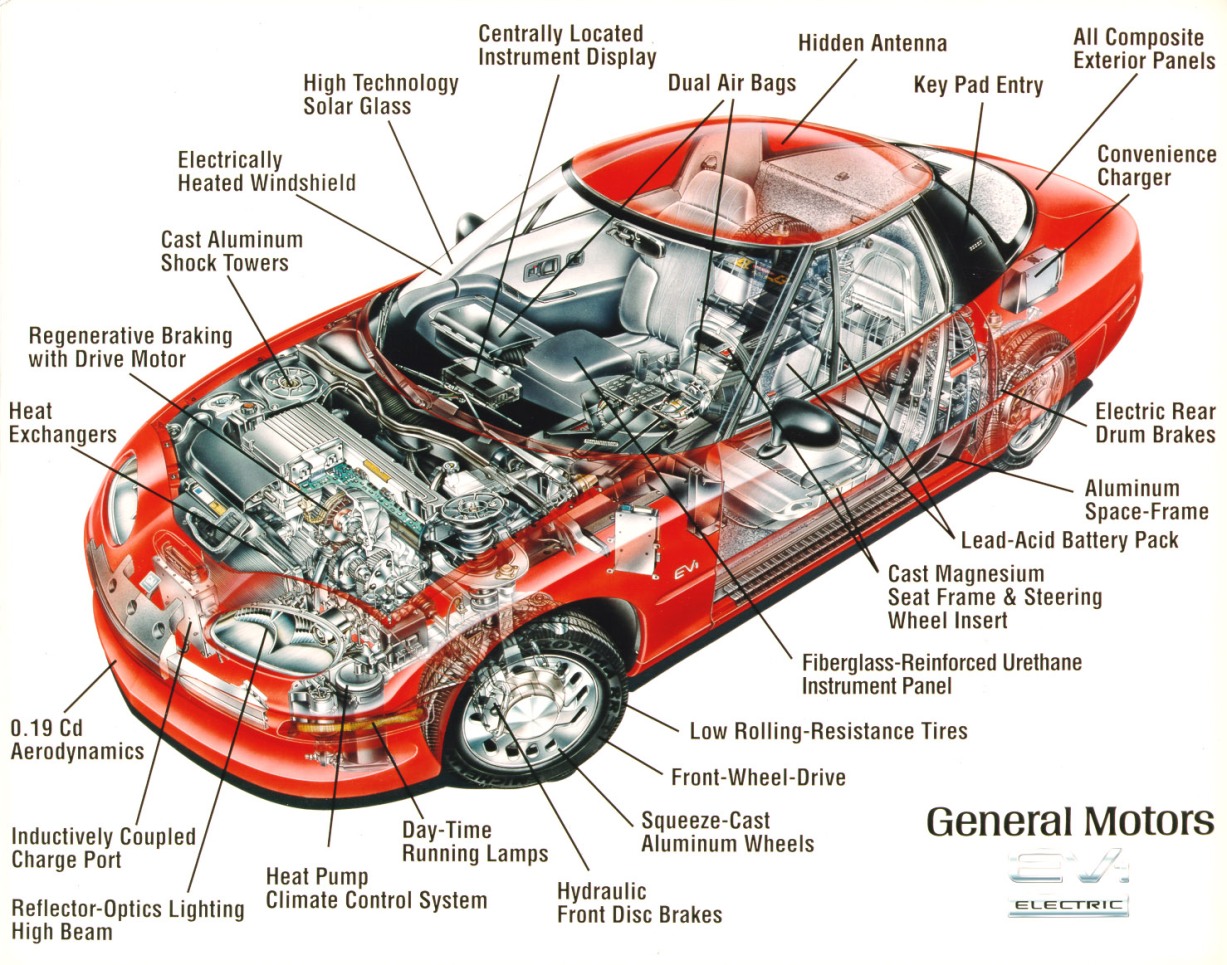

Just to give a little context for those of you not familiar with the EV1: It was an unbelievably advanced electric car built by General motors between 1996 and 1999, and leased to about 1,100 folks, many of whom were celebrities on the west coast. Car and Driver mentions the car’s impressive innovations, many of which are being leveraged to this day in modern EVs (note that some of these aren’t true “firsts,” but all of them were cutting edge):

The list of technologies designed, developed, and put into production by that talented and tireless EV1 engineering force is truly impressive. On the EV1 were many industry firsts and many widely used today in both ICE and EV vehicles. Among the most significant were: power electronics design, packaging, and cooling directly related to today’s EVs; electrohydraulic power steering (EHPS), which soon led to electric power steering; heat pump HVAC (the “grandfather” of today’s systems); low-rolling-resistance tires; inductive charging (now widely used for phones, electric toothbrushes, and other things); an electric-defrost windshield (virtually invisible embedded wiring to defog the glass); keyless ignition (the EV1 used a console keypad); electric brakes and parking brake; by-wire acceleration, braking, and gear selection; cabin temperature preconditioning; tire-pressure sensing; regenerative braking (including variable coast regen—which was on our early development cars but just two set levels selected by a shift lever button on production EV1 cars, due to legal issues with brake-light activation), and regen/friction brake blending; IGBT (replacing MOSFET) power inverter technology, and low-friction bearings, seals, and lubricants.

People loved the EV1, even with its range of only 55 miles or 105 miles (55 with the lead-acid batteries, 105 with NiMH batteries). Back in the 1990s, these were respectable range figures, and the way the car drove — something many people are only now recognizing as they pilot EVs for the first time — was unlike anything most folks had ever driven. The response from that electric motor, the regenerative braking, the silence — it was fantastic.

Look at the graphic above, and you’ll see technologies that were unheard of in the 1990s. The 0.19 drag coefficient still beats that of any Tesla; the cast aluminum strut towers (here’s GM’s patent) were innovative back then, and you could argue might have inspired Tesla’s GigaCastings; low rolling resistance tires were really barely a thing a the time; the heat pump that is so important to modern EVs getting decent range in the winter was super advanced, as well, and wasn’t found in even much more modern electric vehicles like the early Tesla Model 3. Add the aluminum space frame construction, hidden antenna, and optics-headlights and GM had something truly state-of-the-art.

The vehicle was so beloved that, when GM pulled the plug on the egregiously expensive program that, one could argue, was perhaps a bit early given where battery tech was at the time (“I said, ‘Roger, just keep in mind what we have here. We’ve got about a gallon of gasoline worth of energy in those 870 pounds of batteries, and we effectively re- fuel it with a syringe'” is an amazing quote from former president of energy and engine management, Don Runkle, referencing former GM CEO Roger Smith (via Automotive News)), hundreds of people took to the streets. Check out the Washington Post’s 2005 piece, “Fans of GM Electric Car Fight the Crusher,” about a multi-week protest organized after folks noticed EV1s sitting in a lot in Burbank:

Those cars are rarities, the last surviving batch of rechargeable electric coupes built by General Motors Corp. in the late 1990s. Paul and a band of homemakers, people with desk jobs, engineers, Hollywood activists and car enthusiasts are 23 days into a round-the-clock vigil aimed at keeping GM from destroying the cars.

What’s at stake, they say, is no less than the future of automotive technology, a practical solution for driving fast and fun with no direct pollution whatsoever.

The story goes on:

Enthusiasts discovered a stash of about 77 surviving EV1s behind a GM training center in Burbank and last month decided to take a stand. Mobilized through Internet sites and word of mouth, nearly 100 people pledged $24,000 each for a chance to buy the cars from GM. On Feb. 16 the group set up a street-side outpost of folding chairs that they have staffed ever since in rotating shifts, through long nights and torrential rains, trying to draw attention to their cause.

GM refuses to budge, but several factors give those at the vigil hope. The auto industry underestimated the appeal of gas-electric hybrid vehicles, and now the Toyota Prius, Honda Accord Hybrid and Ford Escape Hybrid are selling faster than factories can build them.

Incredibly, despite all of its innovations, the EV1 program was shut down, and GM used very little of the learnings, allowing the Toyota Prius to become the “it” car for environmentalists, selling in absurd quantities and bringing huge wealth and market penetration to Toyota. In typical GM fashion, it was “Hurry up and wait,” and by “wait,” I mean “let everyone catch up.”

This incredible feat or innovation and admiration ended up becoming a PR nightmare for GM, as this San Jose St. University article describes:

When the development cost was averaged among those cars their cost was about $340,000 each. That average cost is not the relevant figure. Of more relevance is what General Motors calls the piece cost, which economists call the marginal cost. That cost seems to have been somewhere in the range of $16,000 to $18,000 in 1992. That would be about $25,000 to $28,000 in 2012 prices. About one half of the piece cost came from the propulsion system. The piece cost does not include the cost of equipment and structures and other costs associated with the enterprise. One can get an idea of what price by noting that the price charged for the Tesla electric car in California is $100,000. Only posturing Hollywood types are willing to pay that price. Quite likely GM would have had to sell the EV1 for $50,000 to $60,000 in 1992. The number they would have sold at such a price would have been minimal. Therefore the decision to not to produce the EV1 was quite reasonable and rational. Apparently GM set a list price of about $34 thousand for the EV1 but they did not sell any because they did not want to do so. A $34 thousand price in the early 1990’s is about equivalent to $50 thousand in 2012.

However the way GM closed out the program was not reasonable or rational. GM called in the EV1’s from drivers who desperately wanted to keep them and GM hauled them to Arizona and crushed them. GM inanely called it recycling. It was a public relations disaster for GM. Alternatively GM could have auctioned them off for probably $20 to $30 million and saved the significant cost of transporting them to Arizona and crushing them. The sales contract could have stipulated that GM would not be responsible for any future costs or accidents due to design flaws of the vehicles. Instead GM incurred a lasting reputation for sabotaging the electric car.

I’ve said it once, and I’ll say it again: I believe GM has the most overall engineering talent of any automaker. If tasked with building a great car, GM will blow the world’s mind. But the problem has always been decisions made not at the engineering level, but at the executive/product planning level. It has always seemed to me like there are amazing engineers eager to make things happen, but product planners/execs who don’t know which cars to build and when. If only the Ford product folks responsible for genius like the Maverick and Bronco and F-150 Lightning were at GM, I cannot imagine the amazing machines we’d have on the road right now.

Three Binders Filled With Gold

But I’ve digressed. It’s time to talk about the hyper-rare GM EV1 service manuals I’ve attained through a back-alley deal out of a 1987 Cadillac Cimarron’s trunk (actually, a gentleman named Bryce Nash was kind enough to sell me these after storing them for decades. Thank you!). Look at these things:

Bound in Saturn binders (Saturn dealerships were in charge of leasing the EV1s, and in some ways the EV1 feels like a Saturn, with its composite body panels), the books cover the following topics:

- Battery and charging system; body repair; body collision

- HVAC; electrical; general information/specifications; special tools

- Propulsion system; brakes; chassis, miscellaneous

I haven’t read through all these books, as they’re about 1,000 pages per binder, but I have leafed through them and gazed at a few images I’d never seen before. Let’s get into it.

A ‘Pedal Feel’ Emulator For The Electric Braking System

Let’s start with the brake system, which is actually quite fascinating. The front brakes are electrically-assisted hydraulic brakes, and you can see the hydraulic lines in the graphic above. The rear brakes, though, are fully electric.

Basically, the EV1 used a brake controller, which works with the “propulsion control module” (this decides when the drive unit’s motor acts as a generator) to blend friction braking and regenerative braking “to maintain consistent braking as commanded, while maximizing the amount of energy returned to the battery through generation.”

The diagram and text below this graph walk through how the electro-hydraulic (front) and electric (rear) brake system works. It’s quite fascinating, utilizing a “pedal feel emulator” (presumably this one developed by GM’s then-in-house supplier Delphi), which features two spring rates (a soft and a hard) to ensure that the brake pedal force-to-travel relationship looks somewhat similar to this curve (this curve isn’t from the service manual, but rather from the previously-hyperlinked Delphi paper):

The way I’m reading this, the system reads pressure in the brake master cylinder to understand how much braking the driver is asking for. The actual brake hydraulics are closed off via solenoids such that the pedal isn’t actually pushing the fluid through the lines to clamp the front calipers. Instead, the brake fluid pressure reading is fed into a control module, which then decides how much current to send the rear electric brake and front electro/hydraulic actuators:

Air-Cooled Lead-Acid Batteries And A Heat Pump

Since I’m going in no particular order, let’s take a look at the EV1’s 312-volt battery back, shall we? It was T-shaped, not unlike the Chevy Volt’s, and featured 26 twelve-volt lead-acid batteries that totaled 16.5 kWh in capacity (in early models like the one shown here):

You can see there are two stacks of batteries with isolators between them:

They’re all air cooled, with a blower motor at the rear of the battery pack, down below, sucking air from ducts at the front of the bulkhead in certain conditions and through the heat pump in the dash under other conditions:

The image above shows air entering through the HVAC heat pump inlet, though you can see the exterior air ducts, which route downward from the bulkhead, here:

Here you can see the housing for the rear blower motor, which is attached to the backside of the battery pack:

Here’s a diagram of the entire cooling system, including the heat pump:

You’ll notice that in the dashboard (that’s the loop on the bottom right of the image above), there’s a “48 volt PTC resistive heater” on the other side of the evaporator. That’s there to assist the heat pump in warming the cabin, when needed. “The interior is heated by a 48 volt PTC resistive heater and heat pump active when any of the ‘HEAT MODES’ are selected on tehrun/lock shifter assembly (RSA) and the outside temperature is less than or equal to 15C (58F),” the service manual reads.

Front Cooling Module

Here’s a closer look at the cooling module at the front of the vehicle:

The Electric Motor Drives The Front Wheels

OK, since this article is on the verge of being a 5,000 word nerdfest (as an engineer, I can’t help it!), I’m now just going to blast through a few other sections of these service manuals without getting too deep into it. Let’s look at the drive motor, which powers the front wheels. To get to it, you have to look under the hood, where you’ll see a “front compartment sight shield.”

Remove that shield and you’ll see the Drive Motor Control Module (DMCM), which has “GM” cast into it:

Removing that DMCM reveals the drive motor in its full glory:

The drive motor consists of an AC induction motor sending up to 137 horsepower and 110 lb-ft of torque through a 10.96:1 (per Motor Trend) single-speed transmission whose output shafts are parallel to the motor’s axis, just like what you’d find in a modern Tesla. Sadly, the repair manuals don’t seem to show the guts of the motor.

The Motor And Power Electronics Are Liquid Cooled

Both the drive motor and the power electronics mounted atop it (the DMCM) are really the only liquid-cooled components in the entire vehicle. See diagram above and the entire cooling system diagram from before.

Because I’m sure you’re curious, the water pump — mounted right near the driver’s side front wheel liner, contains a manifold that one uses to drain the cooling system:

A Solid Rear Axle, An Independent Front Suspension

Let’s look at the suspension:

That’s a five-link, coil-sprung solid rear axle out back with “aluminum end castings and a tubular center section.”

And here’s a look at the front suspension:

As it states, that’s a short/long-arm independent front suspension with a coilover.

Electrohydraulic Power Steering

Now let’s have a look at the steering setup:

The EV1 utilized an electrohydraulic power steering system, meaning there was an electrically-powered pump that compressed power steering fluid and forced it into the steering rack to provide steering assist. This electrically-powered hydraulic pump was mounted to the subframe rail on the passenger’s side and was accessed via the wheel liner:

While an electrohydraulic steering design was fairly novel at a time when everyone simply used their gasoline engine’s accessory drive to power their hydraulic power steering pump, it wasn’t a first, as even the late 1980s Toyota MR2 had such a system.

A 12-Volt Battery Under The Hood

You may be curious if the EV1 had a 12-volt battery like today’s EVs do, especially since the car’s high-voltage pack was made up of a bunch of 12-volt cells. The answer is yes; GM needed a 12-volt system to power the various electronics (wipers, interior lights, headlights, etc.) so they did what modern EV makers do, and installed a tiny 12-volt battery that’s charged by the high-voltage battery via a DC-DC converter (integrated into the DMCM). Here you can see that 12-volt battery mounted to the bulkhead under the hood:

There’s So Much More In These Amazing Historical Documents

There’s so much more in these books that I haven’t even glanced at yet. Check out the shifter!

There’s also lots of info on the ducting under the dash:

Here’s the special triangular tool you need to remove the drive motor:

Here you can see the car’s jacking points:

Here a look at various harness routings:

Here’s an up-close of the water pump:

Check out how the car uses a datum to place each part of the body into an X,Y,Z coordinate to help body-shops make repairs:

= =

Here’s the front cradle/subframe:

Here’s the front end module:

And here the service manual is discussing repair procedures for plastic panels:

I’m excited to keep diving into these service manuals, but I’m already amazed by what’s in here — it’s a truly detailed, granular look at the technology that went into America’s very first viable electric car. This is a rare glimpse at automotive engineering history.

I don’t know if David already knows, but they also made a Chevrolet S10 Electric truck that literally has a detuned EV1 drivetrain; and apparently there were some that escaped the crusher and were actually sold to customers.

Also there are reportedly only 5 fully functioning S10 Electrics in the world and Jared Pink of the Questionable Garage bought one that was originally owned by the United States Air Force and was used on Dobbins Air Reserve Base in Georgia from new and Got it working on a bed full of marine batteries.

His plan is to convert it to run on Tesla Model S battery modules which should greatly improve the range and performance. (He had to get it working on the marine batteries so he could see how the original computers talk to each other so he can create a battery management system to play nice with the original GM electronics, because Lithium ion batteries don’t like being brute force charged like a lead acid battery has to be)

DT’s sensational and idiotic article titles. “…Never-before-seen.documents..” are getting worn out.

How is this possible that these documents where ‘never before seen”?

Didn’t the authors of the documents see these?

Didn’t the editors of the documents see these?

Didn’t the publisher see these?

Didn’t the dealers see these?

Didn’t technicians see these?

Yes, the manuals are probably very rare and have not been widely disseminated, but the claim of the article title is bogus.

The clickbait is tiring and not needed.

I’ve purchased factory manuals before, the content is very similar. Not sure what all the excitement is about.

The fact that the EV1 was implementing new technology is not a function of what is in the service manuals, it was a result of the engineering and decisions that were made in product development.

Technically these service manuals were never meant to be seen by the general public and the fact that GM went to great lengths to basically erase any trace of the EV1 and S10 Electric from their history and how they were built and how they worked lends credibility to David’s excitement.

Good God man go find a Reddit thread to comment on. They’ll appreciate you there.

Sgt. Hulka says lighten up Francis.

“If only the Ford product folks responsible for genius like the Maverick and Bronco and F-150 Lightning were at GM, I cannot imagine the amazing machines we’d have on the road right now.”

I toured the GM design center during my internship in 2008, just before bankruptcy. They had a Hummer-branded Wrangler-fighter that looked like something Michael Bay designed, but it was legit. It looked like a purpose-built rock crawler. (I think it was the HX Concept, or close to it). Who knows what could have been.

“America’s First Real Electric Car”

There were plenty of real electric cars available in America before the EV1. Some roughly a century before.

The first real electric car of the Tesla Era.

At first I was shocked to see David’s enthusiasm for cars with rust-free bodies and nowhere to spray starting fluid that wasn’t the driver’s nose. But this piece and the battery of posts about his i3 have really made me feel the energy generated by his passion for these vehicles.

His work isn’t just about building buzz – it’s obvious that his takes are well grounded and explore both positives and negatives of EVs. While I doubt he would have remained static had he stayed in Michigan, bolting for the West Coast has provided a new outlet for his automotive interests, one he’s embraced even though EVs are often polarizing within the enthusiast community. And one has to admit that California’s car culture makes it easier for him to plug in to the different currents of thought regarding EVs, whereas he might have found himself insulated from them had he stayed in Detroit..

Watt do you think you’re doing using all the electricity puns in one post? It’s really shocking.

Guilty as charged, but it’s getting late here and I’m kinda wired.

Way cool snag.

Thanks for mentioning that the electro-hydraulic steering wasn’t actually a first.

-the Subaru XT6 had it from 1988. I intended to scavenge one from a rear-ended example for my Subaru GL wagon*, but ran out of time harvesting the lucrative air struts so never got it that pump.

*when installing a Weber 32/36 on those, you either did away with the ps pump or rigged a way to work the carb linkage backwards. I ended up just looping the lines from the rack and manhandling the thing. Eh, it worked

In the early-nineties the City of Burbank designated a section near the former Lockheed plant for encouraging EV production, giving tax breaks and hoping new ventures would rush in and make it a Silicon Valley of electric cars. For my employer I built a handful of dash/pedal structures for one taker (we had also made aluminum components for the GM/AeroVironment Sunraycer earlier). Perhaps the GM presence there was an anchor of that whole deal, which of-course E-Vaporated (sorry) when nothing really came of it.

I live in the SF bay area where every other car is a Tesla, and the only time I saw an EV1 was on a trip to SoCal. Definite scifi/futuristic vibes seeing it go down the road quietly.

Who knows what kind of world we could have had if GM had continued down the EV path.

I was fortunate to drive an EV-1 back in the day. My generous next-door neighbor was an EV evangelist and leased both generations of EV-1 consecutively. He let me borrow the latter car for a day and, aside from a few instructions on how to get it to go, the main message was “have fun, let me know what you think.”

It’s obviously been a while but here are a few things I remember that you don’t always read about:

A modern EV-1 with 4 seats and newer tech would have been amazing.

This is a great insight as the EV1 driving experience is pretty much lost to time. A weirdly “you had to be there” car. Good to hear what it was like from someone who was there 🙂

Thanks! We all assumed GM would expand their line of EVs (Saturn dealers were set up for service), so I didn’t drive it thinking I’d never have another opportunity. It was definitely fun, especially since it was a “real” car from a legit manufacturer, not a weird hobbyist conversion like most EVs at the time. But GM would have had to extend the model line to sell in numbers; the EV-1 was tiny and with such minimal cargo capacity it was limited to commuting and small grocery runs, so not much family utility.

When you think of the knowledge lost just from people rotating companies and even internal roles. I can’t imagine the value of the information gained in the EV1 program that effectively disappeared for GM.

Ahem… “— the very first purpose-built, commercially-viable electric car —”

(Pushes glasses up nose)

Aaaaaaaacktually…

https://www.caranddriver.com/features/g43480930/history-of-electric-cars/

I love the part about Clara Ford driving a competitor’s electric car. Just imagine the fights over the dinner table.

Appreciate the link. And not to disparage DT here, yet that was one hell of an oversight.

That lead drawing – the color cutaway also used in the article header – looks like a David Kimble drawing. If you’re not familiar with his artwork, it’s work some time taking a look at his work.

Normally my ADHD won’t allow me to read an article this long, but I’m fascinated by the EV1. Always have been. I remember seeing these things in magazines (I lived in the Midwest as a kid – nobody had an EV1) and just being so enthralled with the idea of an electric car. The future! It’s here! It still makes me sad that GM elected to kill them the way they did. The EV1 deserved better.

Also – unrelated, the “$34 thousand” and “$50 thousand” thing in the San Jose State article drives me absolutely nuts. Especially annoying because they used “$60,000, $50,000 and $100,000” earlier in the same article. Pick a fuckin convention/style and stick with it. Seeing “$34 thousand” just looks stupid and doesn’t read correctly, at least to me. Ok, that’s enough.

Heat pump is 1800s tech, not super advanced

1800s tech, yes. 1800s application, no. Nobody was heating a car or anything else with an electric heat pump before this. It was considered very innovative and new when Tesla became the only manufacturer to use heat pumps like 5 years ago.

They didn’t invent the heat pump but adapting for automotive use was novel.

My point is just that it’s not super advanced. On a $340,000 car it’s certainly not that innovative to add a switching valve and an additional TXV and whatever else is needed for like $50.

I would argue that Tesla using a heat pump isn’t that innovative either from a technical standpoint. The extra development cost just made sense for them in light of their goals.

A heat pump is really just an AC system where your heat sink and heat source are reversed. Adapting an automotive AC system to run as both heat pump and AC isn’t trivial from a hardware release perspective but isn’t that innovative. It’s sophomore year mechanical engineering school thermo, nothing auto companies weren’t aware of. They just didn’t have the motivation to release it

“OK, since this article is on the verge of being a 5,000 word nerdfest”

But I would read 5,000 words, and I would read 5,000 more, if they were on the EV-1….

COTD!

Just to be the reader who read 10,000 words about the EV1

WOW that is awesome how you got those manuals. Honestly, you should copy/scan them and upload it all 😀

GM should be forced to sell the cars they have left, or have them taken thru civil forfeiture.

They didn’t even mention the EV1 during their EV history, when they announced the Ultium shit, something you picked up on and wrote about here.

Their poor decision making, and the way they handled the EV1 program, is proof that they should not have been bailed out. They learned nothing from the EV1, nothing from NUMMI, and nothing from the bailout.

Maybe instead, CRUSH the Silverados and Suburbans. Make them build new EV1’s from scratch and give them to every original lessee that’s still alive.

I thought they crushed all but a handful of EV1s that they kept for museums.

Tracy mentioned a secret stash of them in the article 😛

I deserve that. Admittedly, it was too long for my ADD, so I went into scan mode.

There are a few in the possession of various universities, but all the surviving EV1s were decommissioned and are therefore no longer drivable. GM was so determined to end EV development that they bricked even the spared EV1s.

AFAIK, Jay Leno has got one in his collection. They gave him one, probably under the condition that he wasn’t gonna install a new power train (they removed the motors and batteries of the few that they didn’t crush) and just keep it as part of his collection. I’m just guessing here, I can’t see no other reason why he wouldn’t bring it back to life, given his ressources.

Francis Ford Coppola has one at his Northern California winery along with a Tucker. Jay Leno did an episode where he drove it on Coppola’s private roads.

There is also an EV1 on display at the Petersen Automotive Museum in LA; don’t know if it has its drivetrain.

Oops; he drives the Tucker… Jay Leno’s Garage, Cars of the Future… on You Tube.

It is crazy how innovative GM can be and how easily they can look past that fact and just screw things up. It amazes me that they are still in business. All of their profit seems tied to large, fuel-hungry SUVs and trucks. If the market ever shifts in the other direction, they will be caught flat-footed. This happened in 2008 and I don’t think they have enough divisions to put into bankruptcy to save them.

As long as they have the UAW in their plants and Democrats controlling the fed gov, there will always be a GM. It’s the ultimate corporate insurance policy.

I love this so damn much, it’s so fascinating that you have this.

Sorry, I have only read the opening paragraph so far, but my mind is already blown. David knows what Baywatch is?!?!?! Now back to reading the rest.

Natürlich kennt er Baywatch wegen Hasselhoff.

These illustrate the difficulties of starting new ev car companies. This stuff is hard and the historical knowledge in car companies is hard to duplicate in a start up filled with tech bros.

I’ve been enjoying Jared Pink’s revival of an electric S-10 (an offshoot of the EV-1) over on his YouTube channel. Seems like EV-1 enthusiasts, the few other electric S-10 owners, and even some GM engineers have hopped on board with whatever information they can provide.

I’m sure these aren’t the only EV-1 manuals that still exist, but one wonders about the lost knowledge those thousands of pages contain.

Wow, that is an impressive manual set. I never realized how many new problems they solved. And they didn’t half-ass it by making it work with existing parts. It is almost like GM intended to make a real car!

Can you imagine how many cubic dollars and engineer hours went into the innovative features, tooling design, assembly line setup, and vehicle testing? GM will spend a gazillion dollars just on someone’s pet project only to unceremoniously flush it 5 years later. At the same time they are squeezing their designers and suppliers to pinch pennies out of each car.

Mel’s was the last of the V1 E-nterceptors.

Sucks electrons! 3-phase head! 120 horsepower through the wheels!

Man, I’m so glad somebody got that joke. I should’ve known it’d be the guy named for a Max character! Cheers!

The introduction to the Interceptor in the first Mad Max film is one of my favorite scenes in the film.

“Kick ‘er in the guts, Barry!”

https://youtu.be/8bQzkdK2ha0?t=32

That’s amazing. Write more articles about the EV1 manuals, I want to see more!

Did you actually buy them out of a Cimmaron, or is that a Jason-mainframe-server type of joke?

That rear axle is interesting, those are some big castings. I wonder if they pressed aluminum end sections onto a steel tube in the center, or if it’s welded, and its a fully aluminum solid axle! An aluminum axle would be extremely unusual.