On May 21st, the design world lost one of its great concept vehicle talents, famous for helping bring the Star Wars universe to life. Colin Cantwell died at age 90 from dementia at his home in Colorado. Colin was integral is the initial creation of the key vehicle models for the first released episode of Star Wars (Episode IV: A New Hope, 1977), working with George Lucas to mock up vehicle ideas as director George Lucas worked through the first drafts of the developing story during the time when George was struggling to secure adequate funding to develop the film.

(Editor’s Note: This is a somewhat different post than normal from our Secret Car Designer, who is taking the time to talk about an important vehicular concept designer instead of a design breakdown or insider’s story. Cantwell is legendary, so I’m glad we have this perspective. – JT)

Building The Star Wars Team

Shortly after the box-office success of nostalgic hot rod culture film, American Graffiti, George Lucas pitched his concept for a grand scale space opera, receiving a fiscally conservative investment of $15,000 from 20th Century Fox for initial development of the project. He quickly set to work with the two concept designers he had brought on as his initial team- Cantwell and designer/illustrator Ralph McQuarrie.

Cantwell carried the title as a “space consultant;” his key work experience at that point included his work as an advisor to the media to help news teams explain to the public the activities of the American space program. Lucas hired Cantwell for $20,000, immediately blowing through Fox’s initial suppor; Lucas begrudgingly had to start spending money from his personal profits from American Graffiti.

Years before Star Wars, Cantwell — who had graduated from the UCLA animation school — worked for Stanley Kubrick to create the seminal 2001: A Space Odyssey film. Cantwell was part of the “class of 2001,” that George hired, which included Cantwell’s close associate Douglas Trumbull. Trumbull at the time was quickly becoming known for his skills in visual special effects, particularly in the creation of realistic depiction of spacecraft on film. After 2001: A Space Odyssey, Trumbull directed the sci-fi film Silent Running and brought much of what he learned to George Lucas’s rapidly growing team of talent.

Between Colin Cantwell, George Lucas, and Ralph McQuarrie, the visual world of Star Wars began to take form. Lucas needed several things from Cantwell. He wanted the ability to see what his story ideas looked like as models within the frame of the camera. He wanted designs that could be illustrated by McQuarrie in realistic colorful images to explain the grand idea of the film to Fox. He wanted to draft up a budget for production based on the sets and filming models and effects that would need to be created. and he wanted at the very least to create placeholder design models that could be sketched into action scenes in the storyboards that fleshed out the action of the still-developing script.

Between Colin Cantwell, George Lucas, and Ralph McQuarrie, the visual world of Star Wars began to take form. Lucas needed several things from Cantwell. He wanted the ability to see what his story ideas looked like as models within the frame of the camera. He wanted designs that could be illustrated by McQuarrie in realistic colorful images to explain the grand idea of the film to Fox. He wanted to draft up a budget for production based on the sets and filming models and effects that would need to be created. and he wanted at the very least to create placeholder design models that could be sketched into action scenes in the storyboards that fleshed out the action of the still-developing script.

His Wild Kit-Bashing ‘Models’ Impressed Lucas

Cantwell had already inspired Lucas with his personal project, kit-bash models (kit-bashing was a model creation method that became the standard for sci-fi movie production). Cantwell had created two elaborate kit-bash designs using parts from a sundry of plastic model kits which ended up being critical portfolio pieces that got him hired onto the Star Wars team; a friend of Cantwell’s who had already been working with George Lucas brought him to meet Cantwell and see his wild design creations, and Lucas was immediately sold on what Cantwell could bring to the film.

One design was a steam powered sternwheeler land-ship, which predicted the steampunk trend, and the vehicle designs of Hayao Miyazaki for Howl’s Moving Castle, decades before both.

The other model was a silver treaded machine that again was elaborately built up from the parts dozens of model kits- tanks, trucks, jets, airplanes, battleships, its elaborate detail creating an overall image of mechanical psychedelia. Cantwell called this the “ground superiority vehicle.”

George Lucas’s Space Dragster

Cantwell’s first model built for the film was a generic hero fighter ship which eventually became the iconic X-Wing fighter (shown a few photos below). Lucas quickly explained his idea to Cantwell of a lithe little craft that was inspired by a dragster, and Cantwell set to work building a model from a rough thumbnail sketch. George Lucas had grown up fully immersed in hot-rod culture and had injected a little racing flavor into pretty much every film project he had done, so it was fitting that many of the visual analogies used as a foundation for the vehicles of his new sci-fi project had roots in terrestrial contemporary car culture.

Cantwell built up the X-Wing fighter, which was initially nameless, from a 1/16 Revell dragster model, pill bottles, and mechanical detailing with kit-bash parts. The clustering of fine realistic, but technically obscure detail became known as greebling. The term that originated during the team during the development of Star Wars, but it is not known who came up with the word.

What made Lucas and Cantwell’s designs so iconic was their simple and easily defined overall shape. Cantwell pieced together the X-Wing model with the mental image of a gunfighter drawing his pistols.

The X shaped wing configuration was a brilliant functional reveal idea that Cantwell came up with after thinking about the look of darts being thrown through the air in a pub. The design of the distinctive spaceship was visualized from the beginning as looking exciting in motion.

Taking a close look at the X-Wing model itself, I was not able to determine what the source dragster kit was used for the front fuselage, but many of the aspects- the rounded cowl, the grassy green molded color and long blue stripes suggest it may have been an early version of the Revell “Beebe and Mulligan” dragster.

As a finished model, Cantwell’s X-Wing is a terrific example of iconic shape expression, but also an exercise in balance of detail — the wing areas are very clean styrene sheet structures, in design we call these “areas of rest,” where there isn’t an abundance of detail. Toward the functional areas such as the guns and engines, he added greeble clusters of pipes, tubes, fasteners and stacked panels. The aesthetically beautiful ratio of areas of rest and areas of detail on the wings is similar to the ornamentation of classic architecture. The ornate capitals on top of Greek columns provide the areas of detail while the column itself a simple formed connective structure between the roof and ground (entablature and stylobate, to use technical terms).

This initial model was an important starting point in the process, but the design had to evolve significantly during the production and filming, notably the proportion and bulk. The thin details would disappear at certain angles when the model was superimposed over the darkness of space, and if there was any reasonably affordable plan on building a hangar set with full sized X-wings, the relative size to the pilot would have to get smaller so the wings and nose got noticeably stubbier and thicker.

Completing The Fleet

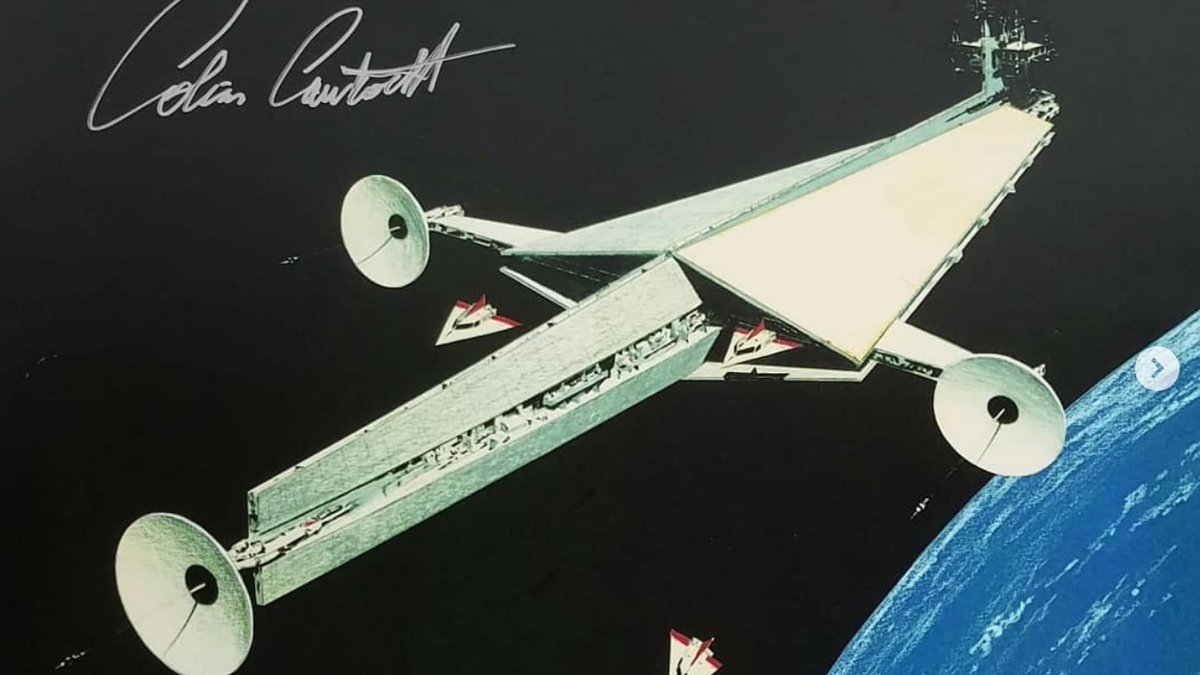

Similar adjustments were necessary to develop the subsequent models produced by Cantwell, but the essence of his initial ideas carried through into the most iconic designs of the movie: the proportions of the hexagonal energy panels of the TIE Fighter relative to the cockpit, the silhouette and overall volumes of the WWII dive bomber inspired Y-Wing, the massive delta shaped star destroyer with its John Berkey inspired battleship command bridge, bristling with sensor arrays. The star destroyer distinctively was directed to be massive. “How massive?” Cantwell asked Lucas. “bigger than Burbank?”

Having created the soul of the X-Wing, Y-Wing, TIE Fighter, Blockade Runner, Death Star, Star Destroyer, and Luke’s Landspeeder, refinements were handed over to the model creation team who tweaked the concepts for production filming models. Cantwell’s models continued to be reference point for the team, Joe Johnston, brought onto the project later to “tighten” up Cantwell’s designs and flesh out the details of the entire universe began his work by referencing what Cantwell had done.

Probably the only spaceship design from A New Hope that was developed after Cantwell’s departure from the team was the Millennium Falcon, another unforgettable shape. Initially, Cantwell had designed a long, thin spaceship with a large cluster of thrusters at the back and truncated conical cockpit reminiscent of a B-29 bomber, but the Gerry Anderson TV series, Space: 1999 came out during pre-production of Star Wars, and the main featured ship bore too similar a character to the Cantwell “pirate ship,” so the team let by Joe Johnston came up with a new dish based motif. (While some tales say the design was based on a hamburger, Joe Johnston claims he was inspired by a pile of unwashed dishes in his sink.)

After his work on Star Wars, Cantwell continued to work creating sci-fi visions on films like Spielberg’s Close Encounters and War Games. It should be noted that aside from Cantwell’s model making skills, he was also a talented draftsman and artist. During his early years as a student, he managed to gain admittance to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin School of Architecture by simply showing up uninvited with a portfolio of work specifically designed to impress Lloyd Wright. Cantwell also was a sci-fi writer in more recent years.

Cantwell’s Star Wars legacy echoed into the 21st Century. One of his early Star Destroyer designs was used nearly verbatim to his original sketch from the 1970s as one of the ships in Solo: A Star Wars Story. His name was used to officially christen the vessel, the Cantwell-Class Arrestor Cruiser.

Cantwell made up a key team, composed of Joe Johnston, Ralph McQuarrie, who ended up influencing a generation of designers who had their minds blown by Star Wars. The sketchbooks and “making of” books were pored over by future designers who went on to careers in product design, concept design, and like myself, car design. Star Wars was not just another movie, but a film and American art cultural experience that changed a floundering movie industry and redrew the standard of what sci-fi could be, given the proper budget and high level of imagination.

Awesome article, really appreciate your lens in looking at the legacy of a great visionary.

Thank you. This is awesome.

The kit-bashing/greebling approach is great because it turns into a treasure hunt for people looking to make replicas later. If you talk to folks making Back to the Future Deloreans, a bunch of the parts that went into that car were just obtanium from the studio storage closets, so if you’re trying to make a faithful replica, you’re having to hunt down the lid to a 1972 Honeywell Home Popcorn Maker or some such thing (although I’m sure it’s all just 3D printed these days).

Yes! I wonder how many vintage Graflex camera flash units have been hacked to pieces to make replica light sabers!

I really tried to track down the dragster kit. Looked at eBay listings and looked at pics of the parts still on sprues. Can’t find it. It may have been snapped up by replica recreators, but I couldn’t even find mention of the kit being used in a recreation. Joe Johnston is quoted as saying it was a Revell 1/16 kit, but I’m not convinced he necessarily remembered the brand. Lots of US companies did dragster kits in the 60s and 70s…

(Editor’s Note: This is a somewhat different post than normal from our Secret Car Designer, who is taking the time to talk about an important vehicular concept designer instead of a design breakdown or insider’s story. Cantwell is legendary, so I’m glad we have this perspective. – JT)

We like this, we want _more_ of this!

I had the great pleasure to meet Mr. Cantwell about 5 years ago at a convention. It was one of the first conventions he attended and was at an unassuming booth so my buddy and I got to have a pretty good conversation with him as entirely too many people obliviously walked by. It’s not too often you get to thank someone for their part in something that played such a big part in my life.

At the risk of sounding like I am speaking ill of the dead…

While the TIE-fighter panels are certainly iconic, as stated in the article, they are a terrible design for an air/space-superiority fighter, especially one without shields. The rebel forces pretty much all had canopies that did not block any reasonable amount of view. Sensors be damned, any pilot worth their salt wants to see what is all around them.

This does not change that this was still an incredible body of work that will last past my generation.

That is a really common sentiment in the Expanded Universe. Authors tried really hard to explain it and find ways around it.

I’ve just started introducing my kids to Star Wars in the past couple of weeks so I’ve gotten to relive some of magic I felt as a 6-year-old watching the original in the theater. It is sad to hear of the passing of a hero of my childhood that I never knew that I had but his work certainly played a massive influence on my childhood and my cultural development.

We watched Empire last night and it was amazing to watch my 7-year-old’s jaw literally drop at “No. I am your father”. I think it is safe to say that even though Mr. Cantwell is no longer with us his influence will be around for a long time.

When I met him (in my post above), I made sure to thank him on behalf of my (the unborn) son. His room was already decorated with Star Wars ships and he could identify the ships before he could talk. I can’t help thinking that being a major part of the creation of Star Wars is pretty close to immortality.

This was great, thank you!

This is wonderful! As an avid modeler who has done his fair share of kit-bashing, and a child of the Seventies who vividly remembers seeing these ships whiz across a drive-in movle screen for the first time (from the front seat of my dad’s ’69 Beetle), this hits me in all the right places. Thank you, and thank you to Mr Cantwell for all the magic.

I got to see some of these models up-close at a traveling museum exhibit many years ago, and was endlessly amused by the presence of a Champion Spark Plugs decal right on the very tip of the nose of the eight-foot-long Star Destroyer model…

One of the most iconic fictional machines of all time can trace it’s roots back to a guy seeing a dart thrown at a board in some bar. That simple, almost child-like spark of imagination is all it took. So cool.